Ari Karpel and David Mermelstein are AwardsLine contributors

From the homemade, unpolished qualities of 5 Broken Cameras and The Gatekeepers to the journalism of How To Survive A Plague and the investigations of The Invisible War and Searching For Sugar Man, this year’s documentary feature nominees traverse challenging and rewarding territory. Here’s a look at the films from which voters must choose.

5 Broken Cameras

5 Broken Cameras

The homemade quality that permeates 5 Broken Cameras is its greatest strength. For what this plainspoken documentary lacks in polish, it makes up for in heartfelt emotion. The film centers on the life of its filmmaker, Emad Burnat, a Palestinian resident of Bil’in, a village in the occupied West Bank near the Israeli border. It opens with the birth of Burnat’s son Gibreel in 2005. Then, paralleling the first few years of Gibreel’s life, the film charts the hardships endured by the village as it copes with the erection of a barrier, built by Israel, that separates Bil’in from its olives groves.

“I just started to film and document my people’s nonviolent struggles in the village in 2005,” Burnat says, speaking recently by phone from Bil’in. “I decided to take part with my camera. I used it for many purposes. I was the only one in my village with a camera. I used it to protect myself and to spread the news to TV. I wanted to make this not like any other documentary. I was filming for more than five years, and then I decided to start the editing.”

Soon the nonviolent protests in Bil’in attracted sympathetic outsiders, including Israeli peace activists, one of whom, Guy Davidi, was also a filmmaker. Over time, Burnat and Davidi got to know and trust each other, resulting in a collaboration that produced this film.

“Of course, I wanted to say something political,” Davidi explains, speaking by phone from Tel Aviv. “But my real message was an emotional journey. In order to change opinions, you have to go through an emotional experience. You may do it through art. If you’re open emotionally to experiences, then you’re shocked and change your ideas. I’m looking to build motivation for change. There are a lot of ideas in the film. And you see how the Israeli side is reacting in a violent, aggressive way to this movement. You see how the government is treating a modest, friendly movement. And yet those Palestinians who are protesting are criticized by other elements in Palestinian society. Both of us, Emad and me, took big risks to do this film.”

Explaining his motivations not just to make this film, but also to do so by working with an Israeli, Burnat says: “People are suffering. Children are growing up here in a very bad situation, not a normal situation. We are the only people in the world who live under an occupation. I want my children to grow up in my home as others do in the world. I want them to have freedom and justice.”

Burnat’s big ambitions for this film might have seemed unrealistic before its Oscar nomination, but now this documentary’s reach has clearly widened. “I hope for this movie to go out and reach every house in the world,” Burnat says. “People can get to know more about our lives and about reality and truth. This is my personal story. I was suffering with my family. I made it very real. This is our life here. I didn’t want to make it like other documentaries, talking about violence and politics. I want people to see the reality. And they will be touched by seeing this story and feel very close to it. We are all human. I wanted to make it so everybody in the world can think together and make change together.”

—David Mermelstein

The Gatekeepers

The Gatekeepers

Dror Moreh’s documentary The Gatekeepers isn’t fancy. But it is sobering. In fact, the director’s unsentimental examination of Israel’s ongoing Palestinian problem gains force because of its simplicity—it’s essentially six talking heads (all the living former heads of Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service) and some elegant reenactments.

Those six men live up to their billing as stoic sentinels of Israel’s precarious security, and Moreh’s achievement is to get them to speak straightforwardly, if sometimes cautiously, about Israel’s untenable occupation of Palestinian territory.

“I wanted to make a movie from the most prominent people who were dealing with the conflict,” Moreh says. “If there’s someone who understands this situation, it’s them. They dealt with the terrorists. If there’s someone who knows about this situation, it’s them.”

The hard part, obviously, was getting security chiefs who made their careers in the covert world to open up in front of the camera. But Moreh had a strategy. “When you are trying to get to these people, it’s not like they have a club where they all sit around drinking whiskey and smoking cigars,” he says. “But I knew that getting one was the key—because if the first one says no, you’ve failed. If the first one says yes, you have a chance.”

That approach worked, though it wasn’t always easy. His toughest “get” was Avraham Shalom—Moreh calls him “the old man”—who ran Shin Bet from 1981 to 1986 and was forced to resign over allegations that he ordered the summary execution of two terrorists following a bus hijacking in April 1984. “He never spoke before—especially after the bus incident, where he gave the order to kill those guys,” Moreh says. “The first interview I did with him—and he said yes only after three meetings—it was like banging my head against the wall. He answered only ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘OK,’ like that. In the second interview, he was more open. Before the third interview, I told him he had to speak about the bus incident. He said, ‘I will see.’ And in the movie, you see me prod him. It was the toughest interview of my life. I was sweating like you wouldn’t believe. When he’s angry, that’s very hard. And you see his look in the movie. It’s really not easy. The confrontation between us is much more fierce than you see in the movie. But after the movie came out, he told me it should have been more harsh on the politicians.”

Moreh says his documentary will resonate with American audiences for various reasons, most obviously because of the historically close ties between the U.S. and Israel. But there are other, more recent, points of tangency, he maintains. “I think there is something parallel in America—the questions of torture and drone assassination,” he says. “Issues raised in my film are relevant to public debate in America—whether such things are morally acceptable. Where are the boundaries? And does it lead to a better future? The strategic question in The Gatekeepers is: What can we do to prevent the next attack? Israel has dealt with this for a long time, and now America is dealing with it. So The Gatekeepers is very relevant to the American people.”

—David Mermelstein

How To Survive A Plague

How To Survive A Plague

David France became a journalist because of the AIDS crisis. “I thought maybe I could find answers,” he recalls of the early, desperate days of the epidemic, when he cut his teeth as a science reporter for the weekly gay newspaper The New York Native, in 1982. France was a witness to the dawn of AIDS activism at a time filled with rage and fear, when members of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and its spinoff TAG (the Treatment Action Group) rattled the cages of the political and medical establishments. “There had been this hard-and-fast rule that you don’t discuss anything about your findings until after peer-review publication,” says France.

Thirty years later, his film How To Survive A Plague, nominated for an Independent Spirit Award and an Academy Award, revisits the small group of people who succeeded in getting drugs approved more quickly—work that helped to transform AIDS from a death sentence into a livable condition. “It’s an unknown story, really.”

Unknown, that is, beyond those present at the time. But even they rarely discuss it. “No one really spoke of it after ’96,” says France, who continued writing about science and went on to become an editor at New York magazine. All the while he held onto the notion that someday he would make a “big project” that would give context to those years. He started off with some magazine articles. “I was surprised by how little people knew about (what had happened),” he says of young readers, gay and straight, whom he heard from across the country. “They were shocked by the herculean effort, the grassroots mobilizing it took to get the system to respond; that gays and lesbians were so disenfranchised; that we weren’t always just talking about marriage.” Those ideas can be empowering to a younger generation, to learn that just a short time ago a group of people were fighting, France says, to be treated as human beings.

His mission articulated, France began gathering video. He remembered that there would be as many as five video cameras present at every ACT UP meeting and demonstration. When he got ahold of one tape, he’d scan it for passing shots of other people with video cameras and track those people down. “That’s how I found more footage.” In fact, he says, “That’s how I got coverage.”

The term “found footage” doesn’t quite do justice to the wealth of video France amassed. “People were using their footage to create important pieces along the way, whether they were art pieces, gay TV journalism for public access cable,” he explains. “Some of it was shot to be brought back to meetings to show what (subgroups) had accomplished.” Often cameras were present as a check on police brutality.

The footage allowed France to craft the film entirely without narration and with relatively few talking heads. Watching How to Survive a Plague feels much like watching the issues unfold in real life, as if you were there.

“There was no way to tell the story without acknowledging the camera,” France says. “The camera itself was a main character in the history.”

—Ari Karpel

The Invisible War

The Invisible War

Kirby Dick is a master muckraker. His first Academy Award nomination was for his 2004 documentary Twist of Faith, which exposed the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church in the face of increasing accusations of child sexual abuse by priests. Dick’s next doc, This Film Is Not Yet Rated, took on a less far-reaching but perhaps no less mysterious monolith of an organization, the Motion Picture Association of America, and its highly secretive ratings board. He then had a crack at Republican politicians who vote against gay rights but who, according to Dick’s 2009 film Outrage, are themselves secretly gay.

Now, with The Invisible War, Dick and Amy Ziering have turned their lens on the U.S. armed forces and the scores of women and men who have been sexually assaulted by officers or fellow service members, and whose lives have been destroyed by the systematic negation of their accusations. The film has earned Dick his second Academy nomination, but more importantly, it is having significant impact on the policies and culture of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines.

Last April, before the film was released in theaters, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta viewed it and promptly executed a shift in policy. He took away commanders’ power to decide whether to prosecute their service members for rape. It’s a massive accomplishment, and yet it doesn’t go anywhere near resolving the issue, a limitation Dick forthrightly acknowledges. “One year of changes is not going to address the problem,” he says. “Panetta did not take it out of the chain of command, so there is still a conflict of interest.” Dick says that putting the issue in the hands of investigators and prosecutors who are trained to handle these things would be the “single most important thing they could do.”

In the meantime, the film has placed increasing pressure on Congress and the Department of Defense to address a problem that is truly staggering in its scope—it’s estimated that half a million women have been sexually assaulted in the military. The film has become the reference point for this issue in the military and Congress. “We’ve had four-star generals tell us that this film told them more than all their briefings in 40 years of service,” says Dick. “Chiefs of staff are using lines right out of the film.”

Dick says that Ziering was instrumental in convincing nearly 50 abused women, and one man, to tell their stories on camera. The result is a shocking collection of accounts. “These interviews were emotionally devastating for us, and equally enraging,” he says. “What the audience feels is what we felt.”

The emotional effect has not been lost on those with the power to change things. “I thought they were going to try to discredit the survivors,” says Dick, who knows from experience that large institutions typically respond to criticism with a closing of ranks. “They tend to react with a powerful P.R. counterattack, but they didn’t because the film made such a powerful case that it’s across the force, in all branches. The people at the top really do care about their soldiers, airmen, and marines.”

He can’t help but conclude: “It moved them.”

—Ari Karpel

Searching For Sugar Man

Searching For Sugar Man

In 2006, Malik Bendjelloul quit his job as a reporter for a weekly arts and culture television show in Sweden to embark on a six-month-long backpacking trek around the world, camera in tow, in search of new stories. He came upon a goldmine of a tale in South Africa.

Back in the early 1970s, when South Africa was under apartheid rule, there was one singer-songwriter whose folk-rock protest music captivated and inspired a white, liberal audience yearning for a new way to live. Rodriguez was the singer’s name. He was an American whose career had failed in the States. But in South Africa, his 1970 album, Cold Fact, was bigger than the Beatles’ Abbey Road.

Still, no one knew anything about Rodriguez. Rumors swirled that he had killed himself on stage. By some accounts he had set himself on fire; others said he shot himself in the head. Either way, it was a gruesome tragedy and it drove Steven Segerman, a Capetown record-store owner known as “Sugar Man,” for one of Rodriguez’s best-known songs, to spend a decade searching for the true story of Rodriguez.

He found more than he’d bargained for. It turned out Rodriguez was alive and well and living in a ramshackle old house in Detroit, oblivious to the legendary renown he had achieved halfway around the world. And he had never seen a cent of the royalties for his South African success.

This is the story that Bendjelloul recounts in Searching For Sugar Man, his documentary that won the Audience Award and a Special Jury Prize at Sundance, the PGA Award, and has BAFTA and Oscar noms for best documentary feature. Bendjelloul tells it pretty much as he learned it, from beginning to end, from rumor to fact, from mystery to revelation. “It’s just beautiful,” he says. “It’s like a Cinderella story, a true Cinderella story, about a man who lives life as a construction worker in Detroit and doesn’t know he’s bigger than the Rolling Stones halfway around the world.”

As the film details, Sugar Man eventually tracked down Rodriguez via the Internet. He told the musician of his success and brought him to South Africa to perform for his ecstatic fans. Since the film came out, Rodriguez’s career has been fully resuscitated. He has appeared on Leno and Letterman, and he’s about to begin a tour of South Africa, one Bendjelloul hopes doesn’t keep the singer from attending the Oscars.

“I was aiming for people to engage on an emotional level, not just cerebrally feel for him,” says Bendjelloul. The emotion of the fans, and of Rodriguez, is palpable in the film. Rodriguez is living the life he’s long been meant to lead, that of a musician singing his truth. “His life is changing,” Bendjelloul says of the 70-year-old musician, “but only in an abstract way. He’s always going to live in that house.”

Bendjelloul finds inspiration in that for his own work. Having made Searching For Sugar Man on a shoestring, he intends to continue that way of working. “I think the key is to try to keep it small enough to be in control, to do what you want to do. Not having people tell you what to do.”

To that end, Bendjelloul says, “I may go travel for six months again.” After all, the world is full of extraordinary stories.

—Ari Karpel

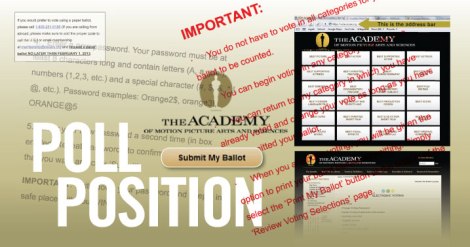

Although all the guilds and other voting groups have moved full force into the world of online voting, the Academy went through a slow, methodical process before finally settling on Everyone Counts, a company known for working with the U.S. government in a similar capacity. Unlike most industry groups, the Academy is a prime target for infiltration by cyber terrorists who would like nothing more than to gain access to vote totals and embarrass the high-profile Oscar process, which in 85 years has never been compromised.

Although all the guilds and other voting groups have moved full force into the world of online voting, the Academy went through a slow, methodical process before finally settling on Everyone Counts, a company known for working with the U.S. government in a similar capacity. Unlike most industry groups, the Academy is a prime target for infiltration by cyber terrorists who would like nothing more than to gain access to vote totals and embarrass the high-profile Oscar process, which in 85 years has never been compromised.