This article appeared in the Dec. 19 issue of AwardsLine.

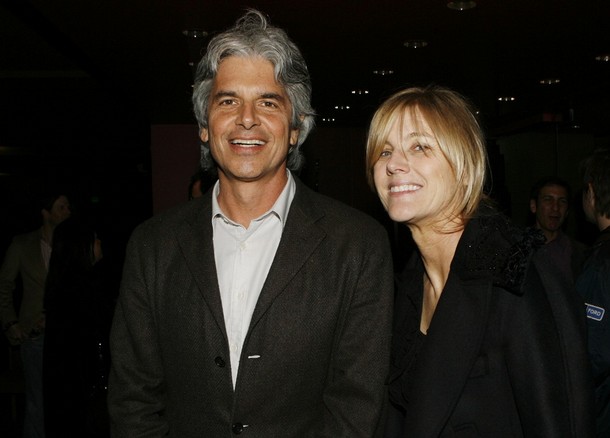

When Walter Parkes and his wife and partner Laurie MacDonald read the first 40 pages of John Gatins’ script for Flight in 2006, the adult drama about a substance-abusing airline pilot piqued their interest. The dark, character-driven story hearkened back to the type of films the major studios used to make on a regular basis. Neither Parkes nor MacDonald envisioned a high-wattage actor like Denzel Washington taking on the role—not only was Washington way out of the price range of a film that needed to be made on a modest budget, their main character worked in a field with few African-American pilots. Nevertheless, once the script made its way to Washington’s agent, the late Ed Limato, the actor read it and was hooked, according to Parkes. “The excellence of a project is no longer enough to get it made: It’s a combination of the quality of the material, the quality of the people making it, and, honestly, the financial circumstance under which the movie is made,” says Parkes, who points out that Washington’s enthusiasm (and, well, severe price cut) helped push Flight to the finish line. Parkes recently spoke with AwardsLine about how it all came together.

AWARDSLINE: Hindsight says that Flight was a great project to take on, but did doing a midrange-budget adult drama give you pause when it first came across your desk?

PARKES: It’s been so long that the business was slightly different then. We first got involved with the project in 2006. John Gatins sent us 40 pages, the only 40 pages he’d written of the project, which only really took us to the crash and the immediate aftermath. While it wasn’t exactly clear where the movie was going, the quality of the writing and the strength of that premise were enticing enough that we felt that, if the script was completed correctly, it would attract terrific elements. And at the end of the day, that is necessary to get a movie like that made. We’re talking 2006, before the (financial crisis) and the way it affected Hollywood. You know, there were many independent labels then—Paramount Vantage would have been a good place for this—but over the course of the development, they pretty much stopped being in business, as did many of the specialty labels of other studios. All that meant was that it was less of a sure bet that the project would get made, regardless of the quality of the script. It really put it upon us to meet certain other criteria—mainly, get really amazing people to do it for very little money. (Laughs.)

AWARDSLINE: So how did you get those amazing people to participate?

PARKES: I wish we could take credit for a lot of it, and we really can’t. Sometimes your job is to keep a project afloat and in the consciousness of the studio, long enough for the right elements to become attached. We worked with John for the better part of 2006 and 2007, and there was a draft, a good draft. There had been conversations with different actors and certain actors chasing it, but there wasn’t the kind of explosive combination that would ignite it as a movie to be made. That really happened because Denzel Washington’s agent, (the late) Ed Limato, had read it and took it upon himself to call me and Laurie and say, “This would be extraordinary for Denzel.” We said, “Great, if he’d be interested…” And about six weeks later, I got another call from Ed saying Denzel read it and he loves it, and he’d love to sit down and talk. So Laurie and I flew to New York, and we had lunch with Denzel. We sat down and Denzel said, “Well, I’m in.” And I said, “Denzel, we don’t really have a director yet.” And he said, “We’ll get a great director.” And I said, “The studio hasn’t said that they’re making the movie,” and he said, “I understand.” And I said, “Denzel, it’s not that kind of movie where everybody’s going to get paid their full rate,” and he said, “It’s a great role, though; it’s a great movie. Let’s see if it can get done.” But still we went through probably a good year having different conversations with different directors. There was a moment there where John Gatins himself was being considered as the director, and Denzel was open to it, but I think for that role he felt that he needed a more experienced hand behind the camera. But it was all done in the very positive way of, “How can we make this work?” I had never thought that Bob would do this small of a movie, (but) it suddenly began to make sense because he’s a pilot, and he was inspired by the screenplay. Once that happened, it felt like we were finally going to make the movie. Even so, there were still fairly stringent financial circumstances that had to be met in order for the movie to be officially greenlit. But, luckily, a director as masterful and experienced as Bob can make a movie like Flight for the price that we made it for.

AWARDSLINE: Did you go in knowing that this needed to be in that $30 million dollar range long before anybody was attached?

PARKES: It’s not our first time at the rodeo. It was not a conventionally commercial project, so the studio would only feel comfortable if we spent “x” on it. It’s not a bad way of approaching interesting and unique material, which was an approach we used at DreamWorks: Use your professional experience to make a best guess (about) a break-even scenario and see if the movie could be made properly under this financial circumstance. Then if you exceed (expectations), the movie is wildly profitable and successful for everybody involved.

AWARDSLINE: The film also walks a careful line in tone with having a somewhat unlikable protagonist. Did you have a lot of discussions with John Gatins about maintaining that balance?

PARKES: There’s an aspect of the character of Whip as portrayed by Denzel that was absolutely on the page: He was charming; he was high functioning; and he had, even on the page, the kind of competence and swagger that we look to in our heroes. So the fact that all of that in a person that was self-destructive, selfish, and teetering out of control just made it more interesting. We were even less concerned once Denzel was cast, because Denzel has pure charisma—no matter how dark he goes, as proven by Training Day, somehow the audience never loses connection with him. I also don’t think I have ever seen him portray fear like this, portray a man who is much smaller than his circumstances. There’s a scene where we’re inside the big meeting with Carr, the owner of the airline, and they’re all talking about, “Is he going to jail?” Through the glass, you can see Denzel, and his knees are together, and he’s in this suit, and his head is frozen down on a magazine that he’s turning the pages of. It’s what you do when just don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing. That kind of vulnerability is just extraordinary.