David Mermelstein is an AwardsLine contributor. This story appeared in the June 5 issue of AwardsLine.

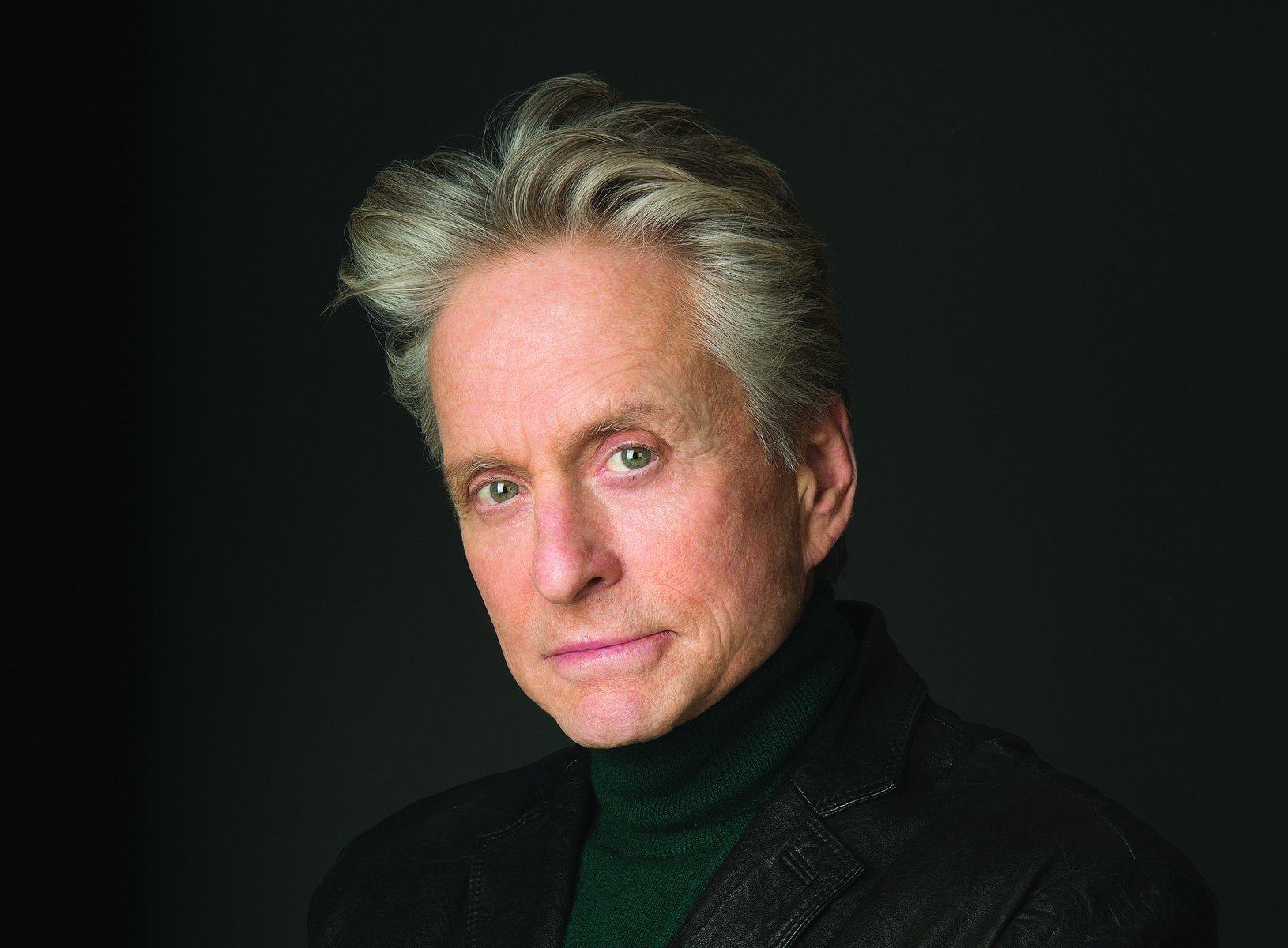

When word first leaked that square-jawed, macho Michael Douglas would star in a biopic of Liberace, the swanning pianist famous for garish costumes and flashy keyboard antics, many feared the worst. But HBO’s Behind the Candelabra—directed by Steven Soderbergh and based on a memoir by Liberace’s lover Scott Thorson (played by Matt Damon)—is anything but an exercise in misguided casting. Instead of camping it up, Douglas, who remains best known for his Oscar-winning turn as Wall Street lizard king Gordon Gekko, embraces his inner queen in an audacious and vulnerable performance.

How were you first approached for the role of Liberace—and what appealed to you about the part?

It’s wild. It goes all the way back to 2000, when I was doing Traffic with Steven. One day he says, “Ever thought about playing Liberace?” I thought he was messing with me. But a couple of times on the set I did an imitation, just for fun. Then seven years later, he called and said, “I’m going to be sending you something.” It was the book Behind the Candelabra by Scott Thorson. Jerry Weintraub had acquired it for Steven, Richard LaGravenese had written the screenplay, and Matt Damon wanted to play Scott. It was a great screenplay with a wonderful character for me to eat up the scenery. My whole career has been me playing contemporary characters, so I welcomed the chance to get behind a figure from a different era. It was like painting on a clown face rather than wiping my face raw for a part. It even required appliances and hairpieces and all that.

Did you actually play piano for the film?

I played, but you wouldn’t want to hear it. I told Steven that for any of the musical pieces I have to play, you’ve got to make sure Liberace filmed them. That way I could copy the actions I saw—you know, get your fingers in the right places. Lee (as Liberace was known to his intimates) had a very distinct style. You spend a lot of hours—a whole lot of hours—rehearsing. That probably took the most hours of anything I did for the picture. And it worked out well. I was really happy with it.

Were you ever worried about descending into caricature?

It was a constant struggle. I was always afraid about being over the top. But Lee was over the top. Sometimes I pulled back, and then it didn’t work. It needed that full commitment. But the tone of the picture allows you that breadth. No one was winking at the camera. We really played it pretty straight, for lack of a better word. But it was an issue we were always conscious of.

You are sometimes made to look ridiculous in the film. Did that ever prick your vanity?

One of the things I was happiest about was that pretty soon we lost Michael Douglas and Matt Damon and saw only Lee and Scott. That’s the beauty of playing a character instead of some extension of yourself.

Your sex scenes with Matt Damon are very intimate. Were they hard to shoot, and how did you prepare for them?

Ha! As Matt and I say, we read the same script, and we knew what we had to do. That’s the thrill of acting, the danger of it. Get your Chap-Stick out, and get ready to rumble. You go for it. We’re actors. That’s what we do. I’m not a boxer or fighter, but sometimes I’ve got those scenes to do. We’ve both had our fair share of love scenes to do, so it’s an extension of that. It was tastefully shot. Steven picked the angles well and didn’t linger.

Debbie Reynolds plays Lee’s mother in the film. What was it like working with her?

It was wonderful because she knew Lee really well. She had great stories to tell about him, and both Matt and I cherished the opportunity to hear them. She knew where all the bodies were buried. It was an enjoyable history lesson.

What was it like working with Steven Soderbergh?

Well, it’s an honor. First of all, he really likes actors, and you can’t say that about every director. Secondly, he’s exceedingly fast, the fastest director I’ve ever worked with. For those of us who like to work fast, that’s good. And he treats you like an adult. He’s a great listener. I just feel really honored to have worked with him a couple of times, and I know a lot of actors who feel that way. He actually shoots his own pictures, so he’s operating the camera as well as the lighting while directing. And he creates this secure, safe world for letting actors do their thing. You feel you can stretch with Steven, rather than withhold or become tighter.

Was there any talk on the set of this being Soderbergh’s last film?

It was talked about in a joking way from time to time. Whenever Matt and I were in a compromised position in the hot tub, we’d say, “This will be great for the final shot of your film career.” Sometimes we’d joke, “We’ll see how long this retirement lasts.” But I think he finished strong with Magic Mike, Contagion and now this. It’s brave filmmaking.