With the awards season is dissected and examined these days, it might appear as though creating a successful campaign is simply a matter of shrewd marketing and a key release date. But even the most cynical strategist will admit that luck is still as much a part of earning an Oscar nomination as anything else. When asked about the plan for a particular film in the awards race, a veteran campaigner said simply, “Light candles, pray.”

Whether they’re already on pundits’ lists or just looking for a little good juju, here’s a look at the films that are in the conversation, not including animation, documentaries, or foreign-language (with a few notable exceptions):

The Majors:

Disney/DreamWorks

Disney/DreamWorks

Last year, Disney’s partnership with DreamWorks yielded two best picture nominees, War Horse and The Help, the latter of which also earned supporting actor Octavia Spencer her first statuette. This year, Steven Spielberg’s followup to War Horse, Lincoln, is considered an all-category heavyweight, from director to Tony Kushner’s adapted screenplay to costumes to production design. And Daniel Day-Lewis’ performance as the 16th president of the United States already has prognosticators declaring best actor in advance of its Nov. 9 theatrical release. Disney also has this summer’s hit from Marvel, The Avengers, which earned $1.5 billion at the worldwide boxoffice and is likely to factor into the below-the-line race.

Paramount

Paramount

It’s going to be hard to top last year’s success with Martin Scorsese’s 3-D love letter to film, Hugo, which ultimately earned five Oscars. But having a Denzel Washington-Robert Zemeckis project nestled in prime awards territory certainly won’t hurt. Flight, which marks Zemeckis’ first live-action effort in more than a decade, stars Oscar winner Washington as a commercial pilot with a substance-abuse problem. The film could be considered a dark horse for best picture, and is getting buzz for screenplay and supporting actor John Goodman. Paramount Vantage also has David Chase’s first post-Sopranos film, Not Fade Away, which follows a group of friends who start a band and features a supporting role from Tony himself, James Gandolfini.

Sony Pictures

Sony Pictures

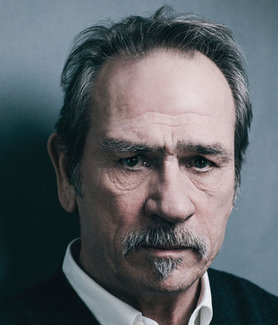

Sony’s big awards-season hopeful is a film with an enviable pedigree: Zero Dark Thirty, which details the decade-long hunt for Osama Bin Laden, is the followup effort of director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal, both of whom won Oscars for their work on The Hurt Locker in 2010. The film is likely to factor into all major categories including lead actress Jessica Chastain, supporting players Jason Clarke and Jennifer Ehle, as well as below-the-line slots. Among Sony’s other films are the new Bond film Skyfall, which has a cast including Daniel Craig, Judi Dench, and Javier Bardem—none of whom are strangers to Oscar—plus an original song from Adele; Rian Johnson’s Looper, which has drummed up small but ardent Internet support; and the August release, Hope Springs, which features Oscar winners Meryl Streep and Tommy Lee Jones.

Twentieth Century Fox

Twentieth Century Fox

Ang Lee’s Life of Pi, which drew early raves when it opened the New York Film Festival, is a visually stunning story about a young man (Suraj Sharma) who’s adrift on the ocean, sharing his vessel with a tiger. Having an unknown in the lead will make it tough to break into the acting category, but it has all the other indicators of a serious all-category contender. Two other potential candidates from Fox’s slate are Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, which could get recognized below the line, and Won’t Back Down, which stars Maggie Gyllenhaal and Viola Davis.

Universal

Universal

All eyes will be on Tom Hooper’s Les Miserables when it starts screening in November, ahead of its Christmas release. Not only are voters eager to see the big-screen adaptation of the musical—which stars Russell Crowe and Hugh Jackman and has a supporting performance from Anne Hathaway—but its unveiling will bring further clarity to the race. It’s likely to factor into all categories (except original score, of course), including for the song “Suddenly,” which was written specifically for Jackman. The studio also has hopes for Judd Apatow’s followup to Knocked Up, This Is 40, which will qualify as an adapted screenplay because it picks up some of the same characters; Snow White and the Huntsman for below the line and original song; and Oscar host Seth MacFarlane’s summer hit Ted, in the visual-effects category; and Oliver Stone’s Savages.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.

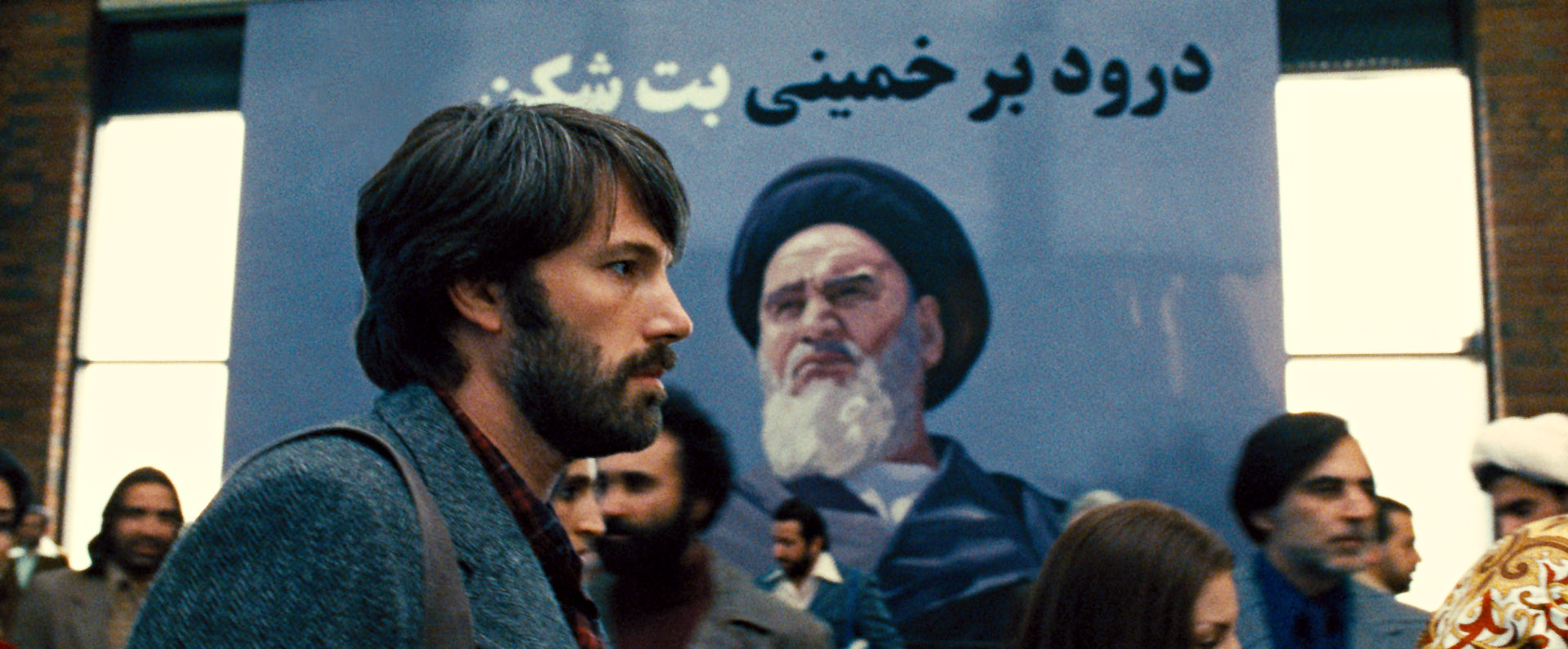

Even with Gangster Squad and The Great Gatsby moving off of Warner’s 2012 slate this summer, the studio boasts a formidable group of films. Leading the pack is Ben Affleck’s Argo, which has been garnering plenty of Oscar talk since its debut at the Toronto Film Festival. Based on a true story, the film will factor into all the major categories, as well as editing, production design, costumes, and music. Not only will The Dark Knight Rises get an all-category push to mark the end of Christopher Nolan’s trilogy, but Oscar winner Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit will be in all of those same categories and hail the start of a new three-film franchise. Tom Tykwer and Lana and Andy Wachowski’s time-bending Cloud Atlas is also being considered an all-category film, with an emphasis on the Wachowski Starship’s adapted screenplay and the crafts categories. Plus, it helps to have a cast of previous Oscar winners: Tom Hanks and Halle Berry in lead, Jim Broadbent in supporting. Trouble With the Curve will get support for Clint Eastwood’s lead role and Amy Adams’ supporting. And finally, for the ladies, Matthew McConaughey will get a boost for his supporting role in Magic Mike.

The Indies:

A24

Shortly before this year’s Toronto Film Fest got underway, former Oscilloscope Laboratories cofounder and president David Fenkel announced his new distribution company, A24. Barely off the ground, the fledgling company is pushing to get into the awards game with Ginger & Rosa, starring Elle Fanning as a teenager in 1960s London dealing with family issues amidst the backdrop of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It’s one of the few films this season directed by a woman, Sally Potter.

Focus Features

Focus’ 2011 awards push earned Gary Oldman his first best actor Oscar nomination for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, plus two others for adapted screenplay and score. And this year, Focus has four films that are a part of the conversation, including Wes Anderson’s Gotham Award-nominated Moonrise Kingdom, which premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and is a likely original screenplay contender. In addition, Joe Wright’s lush, highly stylized adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s classic, Anna Karenina, which is an all-category contender, hits theaters Nov. 16. Keira Knightley is getting attention for her role as the doomed Anna, and the film’s costumes and production design have craftspeople swooning. Focus earned some festival-circuit attention for also Hyde Park on Hudson, which features Bill Murray as President Franklin D. Roosevelt who strikes up an affair with his distant cousin Margaret, played by Laura Linney; as well as Gus Van Sant’s Promised Land, a relatively late addition to the Oscar schedule that stars Matt Damon and John Krasinski, both of whom also cowrote the original screenplay.

Fox Searchlight

With two best picture nominees last year—The Descendants and The Tree of Life—Fox Searchlight is firmly entrenched in the awards game. The specialty division made two key purchases at January’s Sundance Film Festival, both of which have prognosticators buzzing about Searchlight’s prospects for this year. First, Beasts of the Southern Wild, the feature-film debut of director Benh Zeitlin and starring two first-time actors, has earned just over $11 million at the boxoffice since June. Second, The Sessions, is a bittersweet story that stars John Hawkes as a paralyzed man who consults a sex therapist, played by Helen Hunt, which had a solid limited opening in late October. Searchlight’s big hit of the year, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, has grossed $134.4 million worldwide since its May release and features a top-notch cast including Judi Dench and Bill Nighy. And when the November release Hitchcock, directed by Sacha Gervasi, was announced last month as the opening-night film of the AFI Fest, it was instantly clear that the Helen Mirren-Anthony Hopkins picture would be a big part of awards chatter heading into a crucial balloting period.

Indomina Films

This relatively new indie distributor bought LUV, a drama about a boy and his troubled uncle starring Common and Michael Rainey Jr., at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Lionsgate

Earning just over $400 million, The Hunger Games took the summer’s boxoffice by storm. Lionsgate is hoping the Academy will recognize the Jennifer Lawrence-starrer for its crafts achievements.

Millennium

Screeners went out early for Millennium Entertainment’s dark comedy Bernie, which premiered at last year’s Los Angeles Film Festival. The film, which stars Jack Black, Shirley MacLaine, and Matthew McConaughey, is gaining momentum after earning Gotham Award nominations for feature and ensemble. Millennium also has Lee Daniels’ Florida noir The Paperboy, which drew decidedly mixed reviews at Cannes but stars Oscar winner Nicole Kidman.

Magnolia Pictures

The ripped-from-the headlines story in Compliance stars Ann Dowd as a fast-food-store manager who’s manipulated by a caller pretending to be a police officer. Magnolia also has Sarah Polley’s latest directorial effort, Take This Waltz, as well as Denmark’s official foreign-language entry, A Royal Affair, which has an attention-grabbing performance from Mads Mikkelsen.

Open Road

Liam Neeson’s emotional performance in the survival drama The Grey received a lot of attention when the film was released in January, but the actor race is particularly crowded this year, perhaps making it tough for him to break through. Open Road also has the well-received cop drama End of Watch, starring Jake Gyllenhaal, which could get attention for screenplay, crafts, and acting, particularly Michael Pena’s supporting performance.

Relativity

There will be a very targeted effort from Relativity this year for the costumes of Mirror Mirror and Keith Urban’s original song, “For You,” from Act of Valor.

Sony Pictures Classics

It’s rare for a foreign-language film to break into major categories, but Sony Pictures Classics has two that are a topic of conversation. Michael Haneke’s Palme d’Or-winning Amour is appealing to older audiences through its emotional lead performers, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva, both of whom could earn acting noms. Rust and Bone, a Palme d’Or nominee, stars Academy Award winner Marion Cotillard as a whale trainer who loses her legs, for which the visual effects alone are worth Academy attention. On the English-language side is To Rome With Love, Woody Allen’s followup to last year’s Oscar-winning original screenplay, Midnight in Paris; Celeste & Jesse Forever, starring Rashida Jones—who also cowrote the original screenplay—and Andy Samberg; and Smashed, featuring a performance from Mary Elizabeth Winstead that’s getting some attention.

Roadside Attractions

Richard Gere has been well-reviewed in Nicholas Jarecki’s Arbitrage, giving many awards watchers reason to start talking about the actor getting a career-first Oscar nomination. The indie label has hopes in all categories, particularly for Jarecki’s original screenplay. Stand Up Guys, which stars Al Pacino and Christopher Walken, is getting an actor push, as well as one for the Jon Bon Jovi original song, “Not Running Anymore.”

Summit

Juan Antonio Bayona’s The Impossible, which stars Naomi Watts and Ewan McGregor, tells the real-life story of a family separated by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. It’s an all-category contender, particularly for screenplay and its detailed re-creation of the devastating wave. Summit also has The Perks of Being a Wallflower, adapted from Stephen Chbosky’s novel and starring Emma Watson.

Sundance Selects/IFC Films

The long-in-the-making adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s seminal On the Road had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, more than 50 years after its publication. The film, starring Garrett Hedlund and Kristin Stewart, could be a dark horse for adapted screenplay and below-the-line categories.

The Weinstein Co.

Master campaigner Harvey Weinstein is following his best picture win for The Artist with an awards-season slate that includes some of the most renowned directors working today. Although the Gotham Award-nominated September release The Master has divided audiences, there’s no argument that the all-category Paul Thomas Anderson film is visually stunning and has great performances from Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Amy Adams. David O. Russell’s Silver Linings Playbook, which stars Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence, was a crowd-pleaser at the Toronto Film Festival and recently earned an ensemble Gotham Award nom. Quentin Tarantino’s December release Django Unchained, still yet to be screened, is a third all-category film, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jamie Foxx. In addition, multiple Oscar-winner Dustin Hoffman makes his directorial debut with Quartet, about a group of aging musicians in a retirement home that stars Maggie Smith, Michael Gambon, and Billy Connolly; and Brad Pitt has a lead role and James Gandolfini supporting in Andrew Dominik’s Killing Them Softly. The company also has France’s official foreign-language submission The Intouchables, which is being pushed for best picture.