David Mermelstein is an AwardsLine contributor

When we think of Anthony Hopkins, psychopaths naturally spring to mind. After all, the Welsh actor won an Oscar in 1992 for playing Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs, a career-defining role. But, of course, there’s much more to Sir Anthony than just playing brilliant fictional villains. He’s also displayed a knack for portraying complicated historical figures. In addition to playing Hitler (on TV) and William Bligh, the actor has earned Oscar nominations for playing the lead in Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995) and John Quincy Adams in Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997). Now, Hopkins has assumed the role of Alfred Hitchcock in Sacha Gervasi’s Hitchcock, which chronicles the development and making of Psycho.

AWARDSLINE: What attracted you to playing Hitchcock?

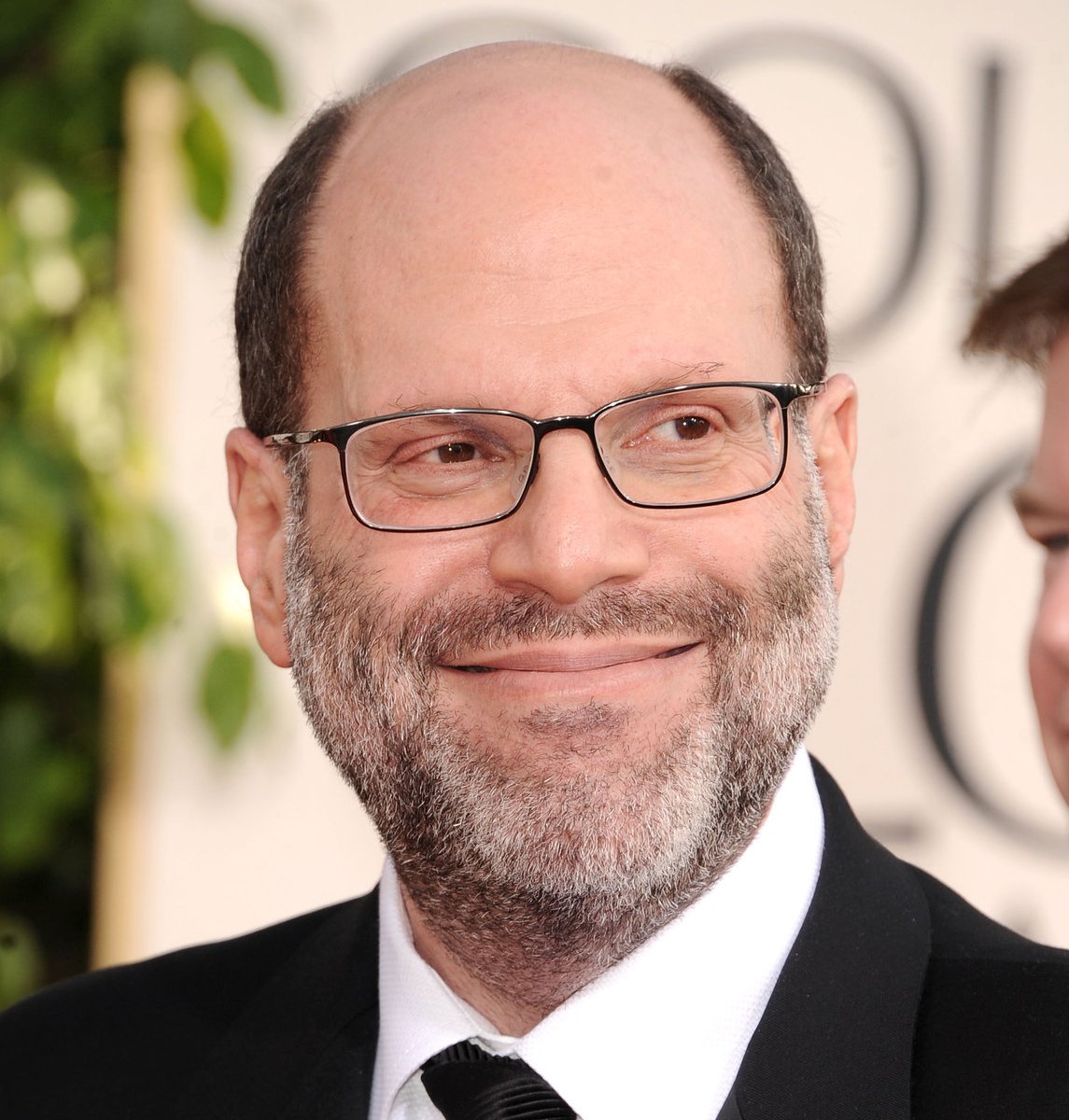

ANTHONY HOPKINS: The project originally came to me eight years. I met the two producers and thought, Yes, it’s interesting. But who wants to see a film about Alfred Hitchcock? Plus, I didn’t want to put on weight, having just gotten fit. So it never happened. But then it came back around. Sacha Gervasi now had it, and he had such passion and blatant enthusiasm for it. He had no experience directing actors, and I thought that would be a challenge. So I decided to just jump in.

AWARDSLINE: Was it difficult acting in a fat suit?

HOPKINS: Hitchcock wasn’t as heavy when he directed Psycho as he was later. We did some tests to get it right. No one wanted me to disappear behind a lot of makeup. They did it from the chin. My jawbone is completely different from his, so it went from my chin to my neck, and then I had the costume. I spent about an hour and half in makeup each day. I also shaved my head, because I’m quite gray, and Hitchcock used dye—that awful red dye. And then, once you get into the mask, I’m not Alfred Hitchcock; I’m Anthony Hopkins playing the guy. So I used what I could. I wouldn’t go on the set till I was completely dressed. I wouldn’t go on in jeans, even in rehearsal. If you’re going to rehearse a scene, become the character. I wanted to feel the illusion of what I was trying to do, and that’s what I did.

AWARDSLINE: You did an enormous amount with your eyes in this role. Was that a conscious choice?

HOPKINS: Yes, it was. I have blue eyes, so I wore contact lenses, because Hitchcock had hazel eyes. The camera has to see behind the lens. I can’t really describe it. Acting is about listening to the other person. You get a great actor like Helen Mirren, and they do the work, and you listen. So when Richard Portnow as Barney Balaban talks harshly to me, it’s just glaring back that I do. Acting is about listening and reacting. John Wayne was right: Acting is just reacting. You don’t have to do much—as long as you stay out of the way of others. That’s why it works.

AWARDSLINE: Hitchcock is a revered figure in cinema, but this film clearly explores his dark side. Why did that appeal to you?

HOPKINS: It’s not so much dark as it’s the complex side of any personality. Hitchcock was such a master of putting on screen things that made you uneasy. Somebody once asked him what frightened him most, and he said the police. He came from a poor background. I think he understood those fears. He hated the thought of sudden violence. He was always wanting to be in control. And his films reflect that at any moment it can happen—your life is in control and then bam. He had such simpatico with the audience. And he was such a romantic, trapped in that obese body but appreciating beautiful women. We gather from biographies that he and his wife had a business arrangement, but we don’t know. He wasn’t an easy man. Janet Leigh said she had fun going to his house because he was such a practical joker. Once an actress told him that this was her best side, and he responded by saying, “My dear, you’re sitting on your best side.” He told Tony Perkins, “Don’t worry about motivation, my camera will tell you what to do.” Tony Perkins asked if he could chew candy on set, and Hitchcock said, “You can do whatever you like, my boy.” Everyone liked working with him. He didn’t say much as a director, but he was clear and supportive.

AWARDSLINE: You also portrayed Richard Nixon. Is there a thrill to playing someone historically important—and how do you refrain from dipping into caricature?

HOPKINS: Nixon is very much like Hitchcock. Both suffered from insecurities, and I know about insecurities and fears. So I understood Hitchcock at an instinctual level. He felt like an outsider, and so do I. I have a little bit of insight into that, so I like playing those characters.

AWARDSLINE: You won an Oscar more than 20 years ago. How did that change your career?

HOPKINS: It didn’t change anything at all. I remember the night I won the Oscar. I thought, Now I don’t have to do anymore. But then you wake up the next morning, and the Oscar is there, and you have to ask, “Now what do I do?” It can be a curse—some actors never work again after winning—but I don’t think about it. I just continue to do my job and get on with it.