While awards voters traditionally underestimate the merits of comedians, Sacha Baron Cohen is the best possible proof that a comedic actor can possess a wider range than his dramatic counterparts. Like his idol Peter Sellers, Cohen arrests stereotypes and authority figures through his iconic personalities (flamboyant Austrian fashionista Bruno Gehard; the blunt Kazakhstan journalist Borat Sagdiyev, and the fierce Middle Eastern totalitarian Admiral General Aladeen as featured in last summer’s comedy The Dictator). However, Cohen has a leg up on Sellers in that his alter-egos brilliantly cross the line, as he throws them into real-life clashes with celebrities and politicians, often exposing their prejudices and shortcomings. Equally balancing Cohen’s outrageous laugh facets is his ability to escape into serious roles, (read his turns as Signor Adolfo Pirelli the Barber in Tim Burton’s adaptation of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, the station inspector in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo). This holiday season, Cohen continues to generate buzz in his second musical role following Sweeney Todd as the duplicitous innkeeper-cum-master of the house, Thenardier, in Tom Hooper’s Les Misérables—a part Cohen takes to another level with his own sense of humor. In 2007, Cohen received a best screenplay Oscar nomination for cowriting Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. This year, he shares an ensemble award SAG nomination for Les Misérables as well as a National Board of Review ensemble win.

AWARDSLINE: How did the role of Thenardier come to you? Was this a project you always wanted to be a part of?

SACHA BARON COHEN: Actually, I only have a history with Les Mis in that when I came out of university at age 20 or 21, I went through an open audition for the chorus in Les Mis—not even one of the named roles. And there were about 300 people who were lining up outside the Palace Theater in the West End, and I passed the first audition, which was singing, and then they had a group audition for dancing, and they taught a little routine. I had no idea how to learn choreographed steps, and so I just decided to freestyle and came to the actual audition. There were seven people doing perfectly choreographed steps and then me just doing some very bad breakdancing in the corner. I did not get the role. So, there is a history.

AWARDSLINE: You’ve also done some musical theater previous to this. You were in Fiddler on the Roof.

COHEN:At the University of Cambridge, I did Fiddler on the Roof and My Fair Lady, and obviously was in Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd. I played Tevye in Fiddler and grew my first beard for that. And in My Fair Lady, I played Alfred Doolittle, which is not a million miles away from Les Mis in that you come on for a little bit, have a couple of nice songs, and then spend the rest of your time in the dressing room.

AWARDSLINE: Was there really this rigorous audition process for Les Mis where the actors had to go in for six weeks?

COHEN: Truth be told, it was slightly brief with me. I heard that Tom Hooper was interested in me for the part, and then I did actually audition. I had to sing—he made me sing a number of songs from Fiddler on the Roof. Even though he actually kind of sprang the audition on me; he came to my house and there’s a guy with him. I asked, “Who’s this guy?” And he basically was a pianist, and then the electric piano arrived, and then Tom made me sing “Master of the House” for him, which I thought terribly unfair because I hadn’t prepared for it at all and hadn’t really sung it since the age of 15 when I first saw it in the West End. It was the humiliation of having to sing a bunch of songs for Tom Hooper in my kitchen.

AWARDSLINE: What were some of the Fiddler songs you sang for him?

COHEN: He made me sing “If I Were a Rich Man,” which, funny enough, I auditioned with for Tim Burton, as well, because when I auditioned with Tim Burton, Stephen Sondheim had to approve all of the actors. Then Tom made me sing all of Thenardier’s songs from Les Mis. I did offer to sing Hugh Jackman’s songs, but he wasn’t interested.

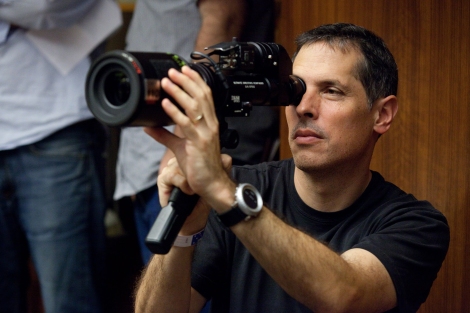

AWARDSLINE: And what’s wonderful is that Tom really gave you room to be you in the role Thenardier.

COHEN: That’s one of his great strengths. I think he’s a fantastic director, but what you get with directors of that stature is there’s a lack of ego, which I also noticed with (Martin) Scorsese when I was doing Hugo. Tom and Scorsese are so confident in their own craft that they’re happy to sometimes give over the reins when it’s a comic number or when there’s a comic side to the piece. So Tom was very happy to listen to every idea and to try and work out something that was different to the stage show and would be unique but also something that could remain authentic to the whole character of the film. I mean what he was worried about was that the piece or two would stand out and would not blend in with the whole genre. So that’s not really worth the challenge. I’ve got to say (singing live during Les Mis) was one of the reasons that I got excited about the project because when I was in Sweeney Todd… when it came to singing my number Tim Burton wanted me to mime along to the track that I recorded a month beforehand. At that point (when I recorded it), I didn’t have a costume; I didn’t really have a fully-formed character, and I didn’t have an incredible set around me with 200 extras. So I pleaded with him to let me sing live because as an actor I need to respond to stuff that’s going on in the moment whether it’s the audience or the actor I’m playing opposite. Particularly jumping off Borat, I wanted to have the song feel authentic. It was a challenge because it was a traditional musical. So I finally convinced Burton to let me sing a couple of takes live and actually they were used. When I first read for the part of Thenardier, Hooper and I talked about (singing live). It’s an exciting idea—singing a musical live—because you can react to things in the moment, and it allows me in the movie to have little asides and throw a little bit of dialogue in between.

AWARDSLINE: I understand Tom Hooper would shoot a song as one long entire take.

COHEN: Yes. This is really challenging, particularly when it’s “Master of the House,” which has a lot of business in it. I mean the problem with these very long takes was that eventually it gets grating on the voice. After a month, I actually lost my voice. And I said to Hooper, and this is actually a testament to him, “Fine, I’ll just mime it. I’ve got the track of me singing, and I’ll just mime it.” And he said, “Absolutely not. It has to be sung live.” And so they shut down the movie. They shut it down for a week during which time I was forbidden from speaking. I was on voice rest. And they brought in Chris Martin’s vocal teacher,who’s the head of voice at the Royal Academy of Music, to train me up again in three days for the “Master of the House.” But when you see the first take of “Master of the House,” it sounds like I’m a drunk guy who’s got a croaky voice but that actually was me with a very croaky voice. Tom Hooper found himself with Helena Bonham Carter and a soft-voiced, stumbling English actor; it was like The King’s Speech all over again.

AWARDSLINE: You’ve mastered the docucomedy whereby you can be a character, interact with real people and elicit a reaction from them. As you became more popular with Borat and Bruno, are these types of films harder to pull off now? Are there places in the world you can still go where people don’t know who you are and pull a stunt off?

COHEN: I mean there probably are places, but the reality is you want to have—when you make a movie like that, you want to make sure that the people you’re interviewing are deserving targets. So you don’t just want to interview some doorman at a hotel; you want to interview the incredibly wealthy guests at the penthouse, high-ranking politicians or people who are threatening. The problem is it is definitely challenging, especially now with Twitter and Facebook. It’s very, very hard to get away with.

AWARDSLINE: Is this one of the reasons why you shifted gears with The Dictator, which was more fictional; still a character but placed in a fictional setting?

COHEN: I wanted the challenge of trying to make a really funny movie that was scripted, but also satirical. I did consider for a while having a Middle Eastern dictator character in the real world, which could have arguably been more satirical to see how people would have done anything for money, you know, which essentially they did with all of these Middle Eastern dictators. There’s a huge hotel in London all the studios use which was built by Colonel Gaddafi, and it’s down the road from the London School of Economics where he was given an honorary doctorate. So essentially these dictators were given carte blanche in any of the western countries that needed their money. It was tempting to take that character into the real world, but I wanted the challenge of creating a comedy script that had improvisation in it as well.

AWARDSLINE: This reminds me of diplomatic immunity whereby foreign ambassadors and their wives, particularly those at the United Nations, have this kind of untouchable privilege here in the states: If they ever shoplift in a store, they can never be prosecuted to the fullest extent of our laws.

COHEN:Yes, dictators certainly have that now. Look around London, and it’s seen as a haven for dictators. With this particular hotel I’m referring to, there are private rooms in the spa for Gaddafi’s children to enjoy themselves in any matter they see fit. What was interesting while making The Dictator were all these organizations that have to show respect to dictatorships, for example, the United Nations. We wanted to shoot a scene there, and they eventually refused us. We asked why, and they said, “Well, we represent many, many dictatorships, and we don’t want to upset them.” So, in the end, we had to re-create our own version of the United Nations. It was ridiculous, really. You know, they said the problem with our movie is that it’s antidictatorship.

AWARDSLINE: In terms of your future projects, you are preparing The Lesbian at Paramount Pictures about the Hong Kong billionaire who offered $65 million to any man who would marry his daughter.

COHEN: Yes, the project about Cecil Chao. I’m working on that at the moment. I’m actually writing a couple of things at the moment and deciding which one to get very excited about.

AWARDSLINE: I have to bring up what happened at the Oscars last year.

COHEN: I can already probably give you my answer before you finish your question.

AWARDSLINE: Was it a publicity stunt, or was it not a publicity stunt?

COHEN: In regards to…?

AWARDSLINE: Admiral General Aladeen appearing on the Oscar red carpet.

COHEN:Well, I mean, Ryan Seacrest was not in on it at all. He was told about an hour beforehand that he would get an interview with me, but he had no idea what was going to happen. He was very excited at the time. In regards to the rest of them, no, it was very real. The Academy did ban me from the awards, and I was. In fact the head of the Academy called up my agents and said if I was to turn up within a half a mile of the Academy he would have me arrested by 200 FBI agents. And then when I turned up as Aladeen, and finally they gave in, the police actually stopped me, surrounded the car, and decided that it was imperative that they search the car. I asked, “For what reason?” and they said, “Well, we’ve been told that you’re bringing in live ammunition into the Oscars.” And so, obviously inside the limo I had a few virgin guards and the urn. I was scared that he was going to go inside and find the urn and ask, “Why have you got Kim Jong-Il’s ashes in your car?” And then I luckily managed to slightly embarrass the cop because I said, “Listen, if you want to search the car, fine. You can strip-search me, and you can strip-search the girls.” And he looked at the girls, got embarrassed, and said, “No, you guys are fine.” You know, the whole thing was very real. With the urn, we asked ourselves, “How are we going to smuggle it into the Academy Awards?” So I decided to camouflage it as a vase. If you actually have a look in the back of one of the video shots, you can see the guy taking off the camouflage and taking away the flowers and turning the flowers into an urn.

AWARDSLINE: Heck, this is show business. It’s a new year, the Academy has a new president, ill will certainly has to have withered since last year’s scenario, no?

COHEN: Listen, I mean I’m a member of the Academy so, I think it’s an important institution. I think it encourages studios and individuals and filmmakers to make great films. Now if it wasn’t for the Academy and the Oscars, there would be less of an incentive to make movies that are not purely boxoffice hits. And in terms of ill will, I’m sure there are Academy members that would not want me back. But, no, I haven’t received anything negative at this time. At the time, they actually threatened Marty (Scorsese) and said that if he didn’t convince me to not turn up, that it would jeopardize the chances of Hugo winning, which is absurd. And by the way Marty responded, “Sacha does what he wants, and if you think I can control him, you’re wrong.”

AWARDSLINE: The sharp comedic and dramatic turns you’ve made between political/social comedies and auteur fare brings to mind Peter Sellers’ career. Is this a career path that you’ve planned?

COHEN: The reality is there’s no plan. I am incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to work with these directors. I remember, I was shocked when I first met Scorsese that he was even speaking to me, let alone I was in the same room with him. I remember we ended up having a meeting, and I thought it was going to be 15 minutes. We ended up spending three hours together, talking about the filmmaking process and just details of editing and writing. So I have been incredibly fortunate to be able to work with these directors, and for me it’s not really a plan each time I’m on a set with one of them. I think about what I can learn from them because I’m very aware that my filmmaking skills are very modest. And so with Marty, for example, I asked him very early on, “Is there any chance I could sit in the tent with you?” He has a little director tent where he watches his work. And he let me in, and for a few months I actually sat by his side and saw the master at work. If you’d told me when I was 20 that at one point I’d be sitting next to Scorsese for a few months and watch him direct I wouldn’t have believed it. Yes, these are incredible moments and there’s no plan. But if there’s an offer I can’t refuse, then I take it. I’ve only done four movies outside of my own: Les Mis, Sweeney, Hugo, and actually Talladega Nights.

AWARDSLINE: I read that you were originally cast in Django Unchained. I’ve got to imagine it was about scheduling in terms of not committing to it as a number of other actors were unable to for that very reason.

COHEN: It was. I was editing The Dictator, and we were very close to release, and Paramount wouldn’t push the date. I knew I’d have to jump straight from there into Les Mis, and it basically became a choice of either pulling out of Les Mis or pulling out of Django. I’m sure Django is an incredible movie, but it was essentially one scene.

AWARDSLINE: What was the role?

COHEN: It was a character by the name of Scotty who Leonardo DiCaprio’s character plays a poker game with. The stakes become Scotty’s slave girl, Broomhilda. [Ed. note: The final cut of Django Unchained doesn’t include the character Scotty, nor a poker game wagering Broomhilda.]

AWARDSLINE: You’re also getting ready to play Freddie Mercury.

COHEN: I am. We’re still working on the script actually. We want to get it right. There’s quite a lot of work on the script.

AWARDSLINE: Aside from what we already know about Freddie, was there anything you learned about him that many people don’t know?

COHEN: Was there anything? I mean, he was a series of contradictions. He was one of the most famous gay men, but he was also essentially married to a woman. He was one of the early celebrities, but he was also deeply private and protective of his privacy. And he was also one of the finest performers and extroverts that ever lived, but also deeply shy. So he’s a great guy to portray. For an actor, you want those contradictions, and they’re kind of a gift for any actor. I hope I’ll be able to do him justice.