Thomas J. McLean is an AwardsLine contributor. This story appeared in the June 19 issue of AwardsLine.

Cinematography that stands out from the TV crowd is now about more than looking better than most other shows—it’s about getting a look that meets the high standards once reserved only for feature films.

But with television schedules and budgets typically only a fraction of their big-screen counterparts, cinematographers on shows such as Mad Men, Breaking Bad, The Good Wife and Vikings use every lighting and camera tool or trick at their disposal to deliver the goods.

Digital technology and the popularity of cameras like the Alexa, which operates well in low-light conditions, have helped immensely, but it still takes creativity to find camera moves and lighting techniques that truly stand out.

Going back to basics has paid off for AMC’s Mad Men. Cinematographer Christopher Manley likes, whenever possible, to drop the second camera typically used to ensure closeups and coverage of every scene. “We set up A shots, and if the B shot can work without compromising either shot, then we’ll use it. Otherwise, we don’t,” he explains.

The result is more medium shots, giving the closeups more impact and evoking a classic big-screen style. “Doing closeups a lot of the time in television is more about a holdover style from when TVs were much smaller and people were sitting in their living room looking at a 20-inch screen 8 feet away,” says Manley. “Nowadays, everybody has a large 16:9 television that dominates their living room, so I think it’s OK to go back to a more old-fashioned scale of using wider shots.”

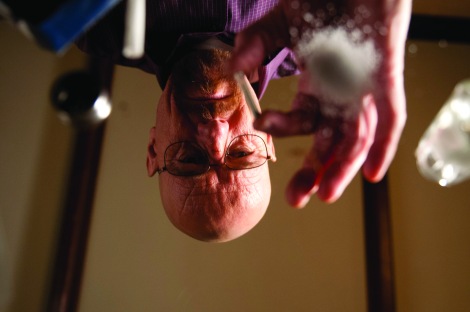

Sister AMC show Breaking Bad goes for the opposite effect, giving itself over to experimentation in shooting. That freedom allows cinematographer Michael Slovis, who joined the show in its second season, to stage all kinds of shots from a one-shot 5-minute teaser and vantage points as diverse as toilet bowls and wine glasses, to shots using macro and periscope lenses.

“The mandate was to tell the story any way that you could, organically, and that expanded our brush strokes,” he says. “We expanded our skill set to a more traditional film approach rather than television.”

The intelligent way the show was set up allowed Slovis to eschew traditional coverage and keep the show on its 12-hour-a-day, eight-day-per-episode shooting schedule.

Another advantage that Breaking Bad had, especially in its early years, was shooting on film—a practical decision that had immense creative payoff. “The autonomy of the camera when we started was really important,” Slovis says. “At the time, you still had to tether digital cameras to a recorder, and it would have slowed us down tremendously.”

Veteran TV cinematographer John Bartley says having most of the scripts for History’s Vikings in hand early on was key to prepping the series shoot in Ireland. Using digital Alexa cameras and soft Panavision Primo lenses, Bartley used cranes, remote cameras and lifts. “We kept it moving all the time,” he says.

Quick lighting solutions are another way to get a cinema-quality look on TV. On CBS’ The Good Wife, cinematographer Fred Murphy uses large-scale lighting and self-lit sets to limit or eliminate the need to relight every shot. “You could move in and shoot the closeup, and the camera could move through the set and there wouldn’t be any relighting,” he says.

On Mad Men, Manley says the lighting has evolved from a studio style to a more naturalistic look, aided by a switch from film to the Alexa in Season 5. “The Alexa allows you to work with less light, and it’s very exciting,” says Manley.

Bartley tapped into the special-effects department to create and manage fires and candles for Vikings as practical light sources, supplemented by fluorescent lights. “I kept saying we could never have enough candles, and they got very good at being able to make them brighter and darker,” says Bartley.

Of course, working on a series has the benefit of standing sets that very quickly become a known quantity for cinematographers and their crews.

“It’s always faster onstage, particularly when you’re working on sets you know inside and out and have worked on many times before,” says Manley. “The danger is that you start repeating yourself, and it can get stale, so I’m always looking for ways to try to keep it fresh.”