This article appeared in the Dec. 19 issue of AwardsLine.

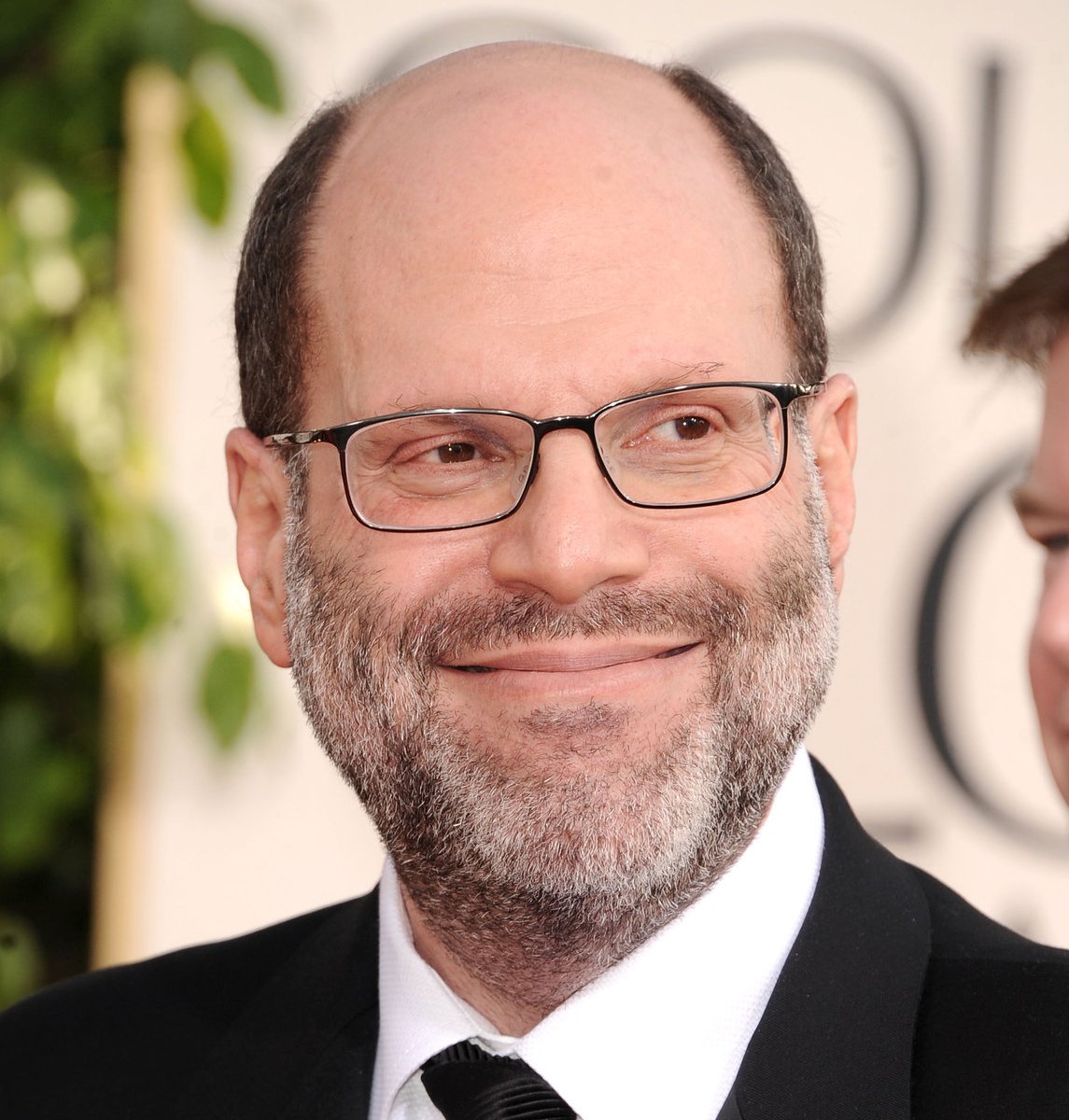

With a long list of collaborators that includes some of the most sought-after writers and producers in the business, Scott Rudin is no stranger to awards season. He’s earned best picture nominations for the last two years running, for The Social Network and True Grit in 2011 and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close last year. He won his only Oscar in 2008 for No Country For Old Men—a year in which his other film, There Will Be Blood, earned a nom for picture—and this year he earned the career distinction of having received all four major entertainment statuettes when he added a Grammy for The Book of Mormon soundtrack. In 2012, Rudin also saw the release of his fifth feature film with director Wes Anderson, the boxoffice hit Moonrise Kingdom. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and has gone on to win a Gotham Award for best film and earn five Independent Spirit Award nominations. Their creatively and financially lucrative partnership continues for Anderson’s 2014 followup, The Grand Budapest Hotel, which reunites much of the same cast and crew from Moonrise, including star Bill Murray and financier Steven M. Rales of Indian Paintbrush. The very busy producer recently spoke with AwardsLine about the film’s success.

AWARDSLINE: You always have a fairly heavy workload for a producer. How do you maintain the quality and still give everything the attention it needs?

SCOTT RUDIN: I have no idea other than there’s no alternative. Honestly.

AWARDSLINE: Wes Anderson said in his AwardsLine interview that he really relies on you in terms of helping shape the material. What kind of feedback did you give him for Moonrise Kingdom?

RUDIN: It’s always, is the story coming across the way he wants it to? Does it have the shape of a narrative in the beginning, the middle, and the end? And are the events landing in a sequence that continues to build on the one before it?

AWARDSLINE: This story is more personal than some of his previous films—does that factor into the feedback you give him?

RUDIN: That’s true, but I didn’t know that when we were working on it. That was never a factor. I would only ever respond to it as a story he wanted to tell. However much of it was personal or not was kind of beside the point of making it into a movie.

AWARDSLINE: Does he usually pitch the story to you, and then you help shape it from there? Or does it depend on the film?

RUDIN: We’ve been in the process for five or six movies, and it tends to be the same on every movie. Sometimes there’s more script when he shows it, and sometimes he does much less—and we work from a lot of conversations.

AWARDSLINE: For this film, what was your role in terms of getting it to the right studio and making sure that the right budget was there?

RUDIN: Steve Rales and Indian Paintbrush financed it, and they’ve done the last few movies, and we always hope to have them on everything. They’ve been fantastic; Steve’s been an incredible supporter of Wes’. Then we talked to a handful of people, and Focus liked it a lot and chased it very hard.

AWARDSLINE: You’re also generally very involved in the marketing of the films that you produce. What were some of the challenges for this particular film?

RUDIN: Realistically, it’s always hard when you make a movie that’s fundamentally about kids for adults. It’s hard to make them work, although this one has worked at a really extraordinary level. But that’s always difficult: How do you make people aware of who the adult cast is without making them feel that the adults are the center of it? Because the adults are really part of the ensemble, but the subject of the movie is the two kids. You don’t want to make it misleading, but at the same time you want to

make it appealing.

AWARDSLINE: And obviously it worked. Why do you think that the film did so well at the boxoffice?

RUDIN: People really respond to what it’s about. It’s a very specific (story), but because it’s so sophisticated, it’s also quite universal.

AWARDSLINE: And it’s been generating awards talk since Cannes.

RUDIN: Well, his movies are executed at such a high level that it becomes an inevitable conversation.

AWARDSLINE: This one in particular has been called more accessible—is that why Moonrise Kingdom is getting that kind of attention?

RUDIN: I think so. And Wes now has made a lot of movies, and he’s a filmmaker with a very loyal fan base.

AWARDSLINE: In terms of your career, you always emphasize that you’re attracted to story not genre, but it seems like you’re also attracted to filmmakers who have a very distinct voice, like Wes Anderson, like David Fincher, the Coen brothers, and Matt Stone and Trey Parker. How do you preserve those voices and serve the project?

RUDIN: I don’t know. I think the job is trying to get the filmmakers to make the movie they want to make.

AWARDSLINE: There’s been a lot of talk about the midrange budget, studio, adult drama—like Flight—connecting at the boxoffice. Has something shifted in the business that makes it more attractive for a studio to take a risk on a film like that?

RUDIN: They’re hard to get done, but they actually can really work. Any movie in which the movie stars work for free, that’s always a big draw. (Laughs.)