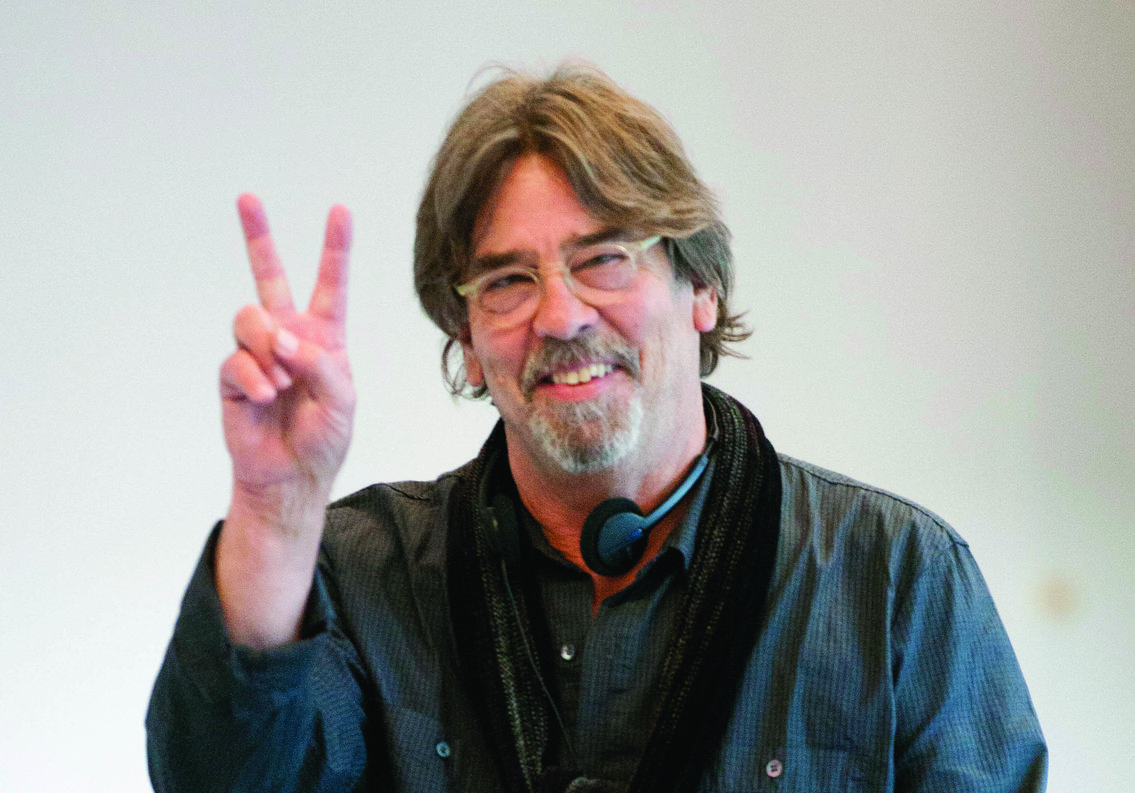

Alex Gansa is executive producer of Showtime’s Emmy-winning series Homeland. This guest column appeared in the June 19 issue of AwardsLine.

On Homeland, we break story as a collective. Which is another way of saying the writers sit in a room for hours and hours until we we’ve eaten so many pistachios there’s nothing left to do but pin some story beats to the wall. It takes a village to construct a thriller, and every writer has a hand in each episode. But for me, writer-producer Henry Bromell’s episode, “Q & A” is the heart of Season 2.

The centerpiece of “Q & A” is Carrie’s (Claire Danes) 16-minute interrogation of Brody (Damian Lewis). In one way or another, Brody has been captive to terrorist Abu Nazir (Navid Negahban) for eight years; Carrie has to turn him—deprogram him, if you will—in 20 minutes. If you don’t believe she does that, the episode (and the rest of the season) falls apart. Every step of their conversation had to build on the previous moment. Every turn had to be clear.

The interrogation was originally three separate sequences, but Henry, the actors, and director Lesli Linka Glatter decided to shoot it as one continuous scene. The first take lasted 26 minutes. Henry turned a procedural into a play, a dance between two people who are lovers and enemies. Carrie wants to know if Nazir is planning an attack on America. The first thing she says? “You broke my heart, you know.” It’s a tactic, and the truth. I don’t think any of us could have written that scene with as much tenderness as Henry did.

Henry could make even the smallest action evocative. One of my favorite scenes from Season 1 is Saul (Mandy Patinkin) alone at his desk. His wife has left him, so there’s no reason to go home for dinner. He’s trying to eat peanut butter and crackers, but he can’t find a knife, so he uses a ruler. He just sits there in the silence, chewing. We got a note from an executive asking, “Why is this scene in here? It’s not about anything.” Henry fought to keep it in. Later, another of our writers was at a security conference in Aspen, full of the people we try to write about. One of them said that peanut-butter scene perfectly captured the late-night loneliness of intelligence work.

Henry’s own life was like something written by Graham Greene. As a kid, he ran into Charlton Heston on the set of Ben-Hur. He went to elementary school in Iran before the fall of the Shah. He hung with Fellini, interviewed Jackie Robinson, wrote for The New Yorker. He had one of those big, far-flung lives people dream about, but his greatest pleasures were simple: Morning coffee and The New York Times with his wife, Sarah; a dry martini; watching his younger son, Jake, happily wreck things.

In our writers’ room, when we we’d get stuck in the mud, he would start in with: “Let’s see, what have we got? Once upon a time…” And he would proceed to spin whatever mess we had made into a narrative that we could listen to and make sense of, and by the end he’d often as not say, “That’s a pretty good story,” and we’d feel OK. Not just because he was a real writer and his approval meant everything. It was the way he did it. He would lovingly separate wheat from chaff, he would hand back to you something better than what he had been given.

Two of our new writers this third season were cajoled by Henry into coming onto the show: Barbara Hall, from Henry’s days on I’ll Fly Away, and James Yoshimura, from his many years in Baltimore on Homicide, where he apparently broke up more than his share of bar fights. They share Henry’s bemused sense of the world.

Henry had started writing Episode 303 when he passed away this spring. We asked his older son, William, who recently started writing for television, to finish the script. Like “Q & A,” the style of the episode is a departure for us. The point of view, pure Bromell.