Thomas J. McLean is an AwardsLine contributor. This article appeared in the Dec. 19 issue of AwardsLine.

Don’t write that obituary for film just yet. The traditional moviemaking format remains a vital tool for the top cinematographers in the field, even as digital technology improves and offers exciting possibilities for the future.

AwardsLine caught up with the men who shot some of the year’s top contenders to talk about how they shot their current films, working with the top directors in the field, and how to make it all come together in the end.

Taking part in our mock roundtable are Mihai Malaimare Jr., who used large-format 65mm film to shoot the majority of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master; Claudio Miranda, who shot the sole digital and 3D picture of this bunch, Ang Lee’s Life of Pi; Wally Pfister, who mixed IMAX and 35mm in wrapping up Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy on The Dark Knight Rises; Rodrigo Prieto, who stitched together multiple formats for Ben Affleck’s Argo; Ben Richardson, who relied on 16mm to capture the Beasts of the Southern Wild for Benh Zeitlin; and Robert Richardson, who reunited with filmophile Quentin Tarantino for Django Unchained.

AWARDSLINE: How did you go about choosing cameras and formats for your current projects?

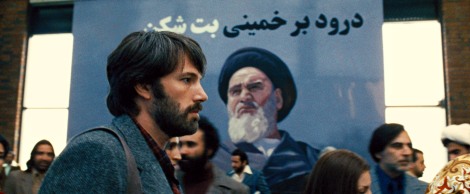

RODRIGO PRIETO: We wanted to differentiate the different segments of the film. We were going to intercut and wanted as soon as you saw an image, say, in Tehran that you would know that’s where you are just by the texture of the image, especially because we were shooting in very different locations.

MIHAI MALAIMARE JR.: From the first meeting we had, we were discussing using a larger format for The Master. The reason is when you think about iconic images from that period, like from the ’30s and right after World War II, you are mainly thinking of large-format still photography. We started with VistaVision, but because the difference wasn’t that big from 35mm to VistaVision, we switched to the next bigger format which was 65mm, and that was giving us kind of the feeling that we wanted.

CLAUDIO MIRANDA: Ang (Lee) was really interested in 3D. He said, “I’ve been really interested in 3D for almost 10 years now. Even before Avatar, I really wanted to see how to bring a new language to cinema.” It had to be digital, because with 3D it had to be really precise.

WALLY PFISTER: Chris (Nolan) sat back and said, “Here’s the deal: This film will stand on its own, but we are wrapping up a trilogy.” We had discussions early on about shooting in IMAX, and I said, “Dude, we should shoot the whole movie in IMAX.” But we pushed up against the limitations of IMAX, which is you can’t record synched sound with an IMAX camera—they’re just too noisy.

BEN RICHARDSON: We instinctively knew that the only viable way for our budget and to get the kind of imagery we wanted was to go to 16mm. The great thing about a 16mm camera, obviously, is that as long as you have a couple batteries and a roll of film and a changing tent, you can keep shooting.

AWARDSLINE: Was it a challenge to make different formats work as a cohesive whole when cut together?

PFISTER: We go through a bit of analysis for what makes sense for that story. The obvious reason for shooting IMAX is because you want to put something spectacular on the screen that’s going to have a visceral impact on the audience. In other circumstances, Chris wants the camera to have a more of a looser, documentary feel. So you use different tools and different formats and different methods to convey the story in different ways.

PRIETO: Once we started testing all these different things, I projected them next to each other, and we saw that the looks were apparent and were visible, but we didn’t feel it was jarring, given that it was all the same aspect ratio. Also, the story has this drive to it that helps it all come together.

AWARDSLINE: How important is having an established relationship with a director versus working with someone you’ve not worked with before?

ROBERT RICHARDSON: I think having an established relationship with a director is unbeatable. The shorthand that comes from a relationship that is longstanding, especially when both sides of the party are respectful of each other, is a tremendous benefit. I’m not opposed to working with a new director, but you do have to approach it differently because you don’t know each other yet. You tend to be a little more cautious.

MIRANDA: You definitely have to figure out where directors will let you go or not let you go, and it’s all about establishing that kind of communication. With Ang, we just talked back and forth about how we feel about lighting, and he let me go a lot.

BEN RICHARDSON: Working with a director I maybe knew less well, we might have had to cover a lot of ground to find the common ground. But I think we had a fairly solid understanding of each other’s wishes off the bat, so our daily conversations in terms of shot lists and shot planning were very much in the realm of an established aesthetic that we both understood.

AWARDSLINE: How did you approach environment and character on your film? Did you see them as separate elements or two parts of a whole?

PRIETO: On Argo, the environment plays a very important role because every situation the characters are in is based on where they are. These environments really affect the characters’ behavior and their emotional states very much in this film. I really tried to support and enhance the sense of this environment and how it’s affecting them.

BEN RICHARDSON: In terms of the environments, we didn’t so much storyboard as follow a shot list. We would go in with a sense of what we needed to achieve, but we would primarily allow the locations and the environments we found to dictate the way certain scenes could feel or could behave.

AWARDSLINE: Give one example or scene that demonstrates how cinematography was used to tell the story.

MIRANDA: I feel like the golden light is kind of a serene moment. He’s throwing this can in the air, and just the way it was captured—we shot it as a very wide shot—and he realizes that in the large ocean this is a really futile idea, and he gets really reflective. He has a little peek at the tiger, and they have a little eye connect. I feel like that was a pretty cinematic moment.

PRIETO: The one that came to my mind is when the houseguests are at the bazaar. I think the cinematography there was using the light to express this feeling of vulnerability, of being scared, and they’re overexposed—the light was several stops overexposed.

AWARDSLINE: With so many digital environments used in movies today, how do you collaborate with the digital artists who are doing everything from effects and environments to color grading?

BEN RICHARDSON: If we had been able to, we might have gone as far as trying to find a way to do a photochemical finish. So it was very important to me that that sort of photochemical feel be preserved all the way through, and I worked very closely with our DI (digital intermediary) house to do a workflow that basically emulated the way you did a traditional answer print. In regards to the visual effects, I had been a key part from the beginning in terms of figuring out how we were going to do those scenes with the beasts. I was very much in touch with Benh (Zeitlin) and the visual effects supervisor as we worked on that stuff because to me that really was the fantasy high point of the film.

PFISTER: As cinematographers, we light in a very—at least I do—visceral, gut kind of fashion, like I’m throwing paints on a canvas. The visual effects guys, they analyze lighting, and they try to re-create it, so it’s much more of a technical process for them, but they’re really starting to understand it now. Their work has gotten better and better, so for me it’s just looking at the end and commenting on whether it’s matching or not.

MIRANDA: I stayed involved in the DI. Bill Westenhofer, who did the visual effects, was there. Even the editor was there, and he was very involved in the 3D because he had made a lot of choices in the Avid for 3D placement and staging and correcting.

AWARDSLINE: What makes your job easier? What makes it harder?

ROBERT RICHARDSON: The most difficult thing would be to have a script that hasn’t yet solidified. To work with something that is in fluctuation continually can be a horror show.

PFISTER: What makes my job easy is working hard. The hardest part of the job is really if people around you are not working as hard as they should be.

AWARDSLINE: What is the most exciting development in the field? What has you most excited about the future of cinematography?

ROBERT RICHARDSON: I’m excited by the movement toward digital cinematography. I think it’s opening up opportunities for a re-evaluation of lighting, and I don’t mean in the sense that it looks like a reality show, but you can work at lower levels.

MALAIMARE JR.: I think this is a really interesting moment because you can still shoot on film for projects that you think will work on the format or you can shoot digital. What’s even more interesting is the fact that you can find really cheap digital cameras—that doesn’t necessarily help the cinematography, but it helps the audience because they are going through a self-training process. The audience is getting more aware of what capturing or creating an image can be and, of course, they have higher expectations because of that.