ACT OF VALOR

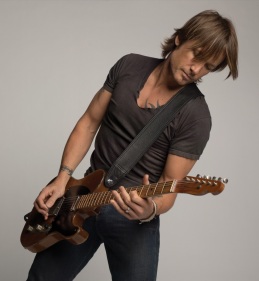

“For You,” Monty Powell & Keith Urban

After watching Act of Valor, country music icon Keith Urban sat down at his Nashville home with his cowriter Monty Powell to discuss their feelings about the military action film they just saw; an anomaly that specifically cast active U.S. Navy Seals performing fictionalized missions.

“I asked myself, ‘Was there something I would die for?’ Certainly, in my case, it was my family. That was the spirit of the song for me,” explains Urban about the film’s sacrificial theme. “It’s easy to watch a military film and have an opinion, but for me it wasn’t about those things, rather, if I had to take a bullet, I would do it for them.”

It was that kind of heart that brought soul to the end-titles song for Relativity’s hit winter film ($70 million), not to mention resonating with Urban’s fanbase and sending “For You” to the No. 6 slot on Billboard’s Country Songs chart.

When writing the opening lines of “For You,” the duo drew inspiration from a moment in which one of the Navy SEALS jumps on a grenade and gives his life for the team. “We decided to start the song seconds after he died, and that if he came back from the dead, here’s what he would have to say,” explains Urban.

Urban and Powell used banjo to construct an up-tempo signature riff to pull the listener in before segueing to acoustic guitar and climaxing with a Strat guitar solo to “respond to the epic landscape of the music,” says Urban.

Shooting the music video proved exhilarating, as a number of the Bandito Brothers production crew reconvened on the original California desert site, the Silurian Dry Lake, where they shot Act of Valor four years prior. A particular high point during the video was the detonation of explosives in the background of Urban’s performance.

Given the amount of music-themed films that his wife, Nicole Kidman, has headlined, Urban looks forward to contributing a track to one of her projects down the road. In fact, director Lee Daniels reached out to him about the possibility of contributing a song for Kidman’s latest movie, The Paperboy. But when you’re a country recording artist with 15 million album sales under your hat, a world tour, and American Idol judging duties, timing is key.

—Anthony D’Alessandro

CHASING ICE

“Before My Time,” J. Ralph

Composer J. Ralph, who has scored two Oscar-winning documentaries, The Cove and Man on Wire, was drawn to his latest project by a somewhat difficult challenge. In working on the climate-change doc Chasing Ice, he wanted to bring a voice to the ice.

“I wanted to create an awareness of feeling, a spiritual and visceral projection of the ice breaking up,” says Ralph, who enlisted the vocal talent of his friend Scarlett Johansson for the title track, “Before My Time.”

Johansson is paired with violinist Joshua Bell on the song, which brings an emotional close to the powerful examination of the changing glaciers. “I wrote the song as a meditative and endless look at the feelings we face daily when governments and corporations neglect the changes in climate control,” Ralph says. “Scarlett provided the Mother Earth feeling that I wanted to express in the song. She knew where to find and emphasize the specific emotional beats in the tune. The one instrument that spoke to me was the violin, and that’s where Joshua Bell complemented Scarlett’s voice so well. Her voice and his violin are the only two instruments you hear on ‘Before My Time.’ ”

Ralph admits he was tempted to ask Carly Simon or other well-known singers he’s worked with to sing “Before My Time,” but the first person he played Johansson’s vocals for—rock legend Stephen Stills—echoed his enthusiasm. “She can really sing and knows how to act out the song,” Stills says.

Ralph, who would love to write an original score for a feature film, realized from the beginning of Chasing Ice that audiences would have to pay attention to the scientific details discussed on screen. “You can have any opinion you desire on climate control, but when you see glaciers physically disappearing before your eyes, it’s hard not to be emotionally moved,” he explains. “The movie grinds to a halt at the end then becomes surreal, so the song gives clarity to the audience. I wanted the lyrics to say that you can’t protest or think you are bigger than Mother Nature. Just look at the news footage of Hurricane Sandy.”

—Craig Modderno

LES MISÉRABLES

“Suddenly,” Alain Boublil & Claude-Michel Schönberg

After nearly 30 years and one of the longest runs in musical history, the much-touted film version of Les Misérables includes a new song, penned and composed by the musical’s original lyricist, Alain Boublil, and original composer, Claude-Michel Schönberg.

Both Boublil and Schönberg are quick to credit the notion of adding a new song to the film’s director Tom Hooper, who’d pinpointed a chapter he wanted to incorporate from Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, upon which the eponymous musical is based.

“It is the first time Jean Valjean meets the young Cosette, just as he rescues her from the Inn of the Thénardiers,” explains Boublil. “We called the song ‘Suddenly’ because (Jean Valjean) suddenly discovers the world is not all bad, it’s not about revenge and hatred. Hugo described how two people who’d been unhappy—the girl and Jean Valjean, who was in jail for 19 years for nothing—can come together to create happiness. This song is a discovery of love.”

“There’s a good reason for this very tender, very moving song,” Schönberg adds, “and it’s much easier to show this on the camera, with a hand stroking the head of a little girl, than it is to capture that (detail) on stage.”

Both Boublil and Schönberg started out as pop songwriters in France, and throughout their three decades of collaborating—which also included the musical blockbuster Miss Saigon—their process has remained unchanged. First, they discuss at great length what a song is going to be about, then Schönberg composes the music, and last, Boublil writes the lyrics.

Both claim they’ve always been open to a film version of their musical Les Mis, but nothing ever came to fruition. “We went as far as we could, but projects have their own strength, they carry on or they don’t,” says Boublil. Then they were introduced to Hooper, who’d just won the Oscar for The King’s Speech. Hooper insisted the film version of Les Mis be the musical in its entirety and not a movie crafted around songs. He also insisted it be shot live rather than lip-synched, which had been the standard method for filming songs.

“We were working with a director for a new medium with new avenues for ways things couldn’t be said on stage,” Boublil says.

Aside from the addition of “Suddenly,” the film remains true to the original musical. “No songs have been removed,” assures Boublil. “That would have been a sacrilege.”

—Cari Lynn

SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK

“Silver Lining,” Diane Warren

“When it comes to the Academy Award, I feel like Susan Lucci,” jokes songwriter Diane Warren, who has six best song Oscar nominations but no wins. Her last nom was in 2002 for a song featured in Pearl Harbor, but Warren has a good chance again this year for penning “Silver Lining,” the romantic theme song for director David O. Russell’s offbeat comedy-drama Silver Linings Playbook. Warren’s lyrics, performed by Jessie J, highlight a dance-rehearsal scene between Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence at a crucial moment late in the picture.

Though she wasn’t able to see the completed film before setting to work, Warren says she loved the script. “As soon as I read the script, the computer in my brain started putting together the song, which was a little more up-tempo and soulful and more retro than the version in the film,” Warren explains. “The idea was to show an important change in the temperamental relationship between the two leads that reflected the fun and romantic joy of going crazy.”

Warren’s hardest problem was convincing executive producer Harvey Weinstein to let her friend Jessie J sing the song in the film. “Harvey kept saying, ‘Get me Beyoncé or Adele.’ Harvey wanted a name, a star to sing it. Later on, he suggested turning it into a duet with Bruno Mars and any female singer the public would know. When Jessie J closed the Olympics, Harvey, to his credit, claimed she was now a star and gave us permission to use her.”

Warren, who has written songs for three different testosterone-driven Jerry Bruckheimer-produced action films, enjoyed the challenge of writing for a gentler film. “You get big-bucks royalties from writing songs for extremely popular male-bonding movies like Con Air, Pearl Harbor, and Armageddon,” she says. “This time, it was nice to do a zany romantic song that showed more of my

feminine side.”

—Craig Modderno

STAND UP GUYS

“Old Habits Die Hard” & “Not Running Anymore,”Jon Bon Jovi

When Jon Bon Jovi received an Oscar nomination almost 22 years ago for his composition “Blaze of Glory” from Young Guns II, he didn’t think it would take him that long to try again. “I was watching an awards show earlier this year, and I thought to myself, Why haven’t I written a film score lately? Oh, yeah, it’s because I made six albums in the past decade, and I forgot about my film work,” he says, somewhat amused at his benign neglect of his scoring and promising acting career. (Though he had a small part last year in director Garry Marshall’s New Year’s Eve.)

But Bon Jovi has finally turned back to his film work, writing two songs—“Old Habits Die Hard” and “Not Running Anymore”—for the gangster movie Stand Up Guys, starring Al Pacino and Christopher Walken. Though he wrote them off the script prior to shooting, the New Jersey rocker’s follow-through was quite unconventional. “Originally, I played my guitar and sung my songs on my iPod for the filmmakers. Then, when they started shooting, I went on location, and I became these guys in my head. I was very low-key and absorbed the atmosphere to fine-tune the songs, which are very specific to the action onscreen.

“The funny thing is, I love writing songs for films,” Bon Jovi continues. “My band is very supportive of me doing this because it teaches me humility. Musicians are in awe of actors and both respect each other’s craft. After he saw the film, Al wrote me a nice letter saying it was the best song he heard in a movie since Bang the Drum Slowly. That’s the kind of compliment that makes me want to do more movies.”

Bon Jovi admits his life would change a bit if either of his songs were to get attention from the Academy. “I may have to shift some things since my band will be on the road then. I can afford to give up the day job (for that)!”

—Craig Modderno

WRECK-IT RALPH

“When Can I See You Again?”Adam Young & Matt Thiessen

When Adam Young received a call from Disney Animation asking him to pen an original song for the animated film Wreck-It Ralph, it almost seemed too good to be true. It hadn’t been that long since Young was an anonymous kid experimenting in his parents’ Minnesota basement with some keyboards and his computer, then uploading the resulting songs to MySpace. A longtime fan of Alan Menken, who scored Disney’s Aladdin among others, Young was told it was his electronica sound that would be a perfect fit to close the 3D film about videogame characters.

Tapping his friend and frequent collaborator Matt Thiessen, of the Christian rock band Relient K (the two are so close they refer to each other as Brother Bear), they were shown only a handful of storyboards and the last five minutes of the film. “(Disney) said, ‘We don’t want to show you too much because that can sometimes be counterproductive,’ ” Young explains. “I agree, and it was great to have just broad strokes and the general feeling.” Thiessen, too, felt that the sentiment in the clip was enough to inspire, and they set about creating a song that was optimistic but somewhat open-ended.

On past collaborations, they worked together in the same room, but this time, they were both on separate tours with their bands so they had to make do. “Adam cooked up a track and sent it my way, and I started singing over it, then sent it his way,” says Thiessen, who wanted to focus the lyrics around the exploration of new worlds, of getting out there and living. The track went back and forth via email as they both changed and added elements, and an MP3 demo eventually went to Disney.

“They were very open-minded to how rough the quality was,” Young says. “They weren’t quick to criticize anything, which I hadn’t expected because there’s nobody who does this better than they do.”

When asked about the Oscar buzz surrounding their song, both were genuinely humble. “It’s hard to grasp what it means just to have a song in a Disney Animation film,” says Young, “and you can see it in the theater and see my name in the credits. To bring in the subject of Oscars, it’s crazy.”

“It’s one dream outshining another dream,” says Thiessen.

—Cari Lynn