Diane Haithman is an AwardsLine contributor. This article appeared in the Dec. 5 issue of AwardsLine.

One thing’s for certain about Flight: The Robert Zemeckis-directed drama starring Denzel Washington as an alcoholic pilot will never be a popular in-flight film. “After this movie, people are going to be waiting out on the steps for the pilot with a Breathalyzer test,” Washington recently joked in an interview.

Flight screenwriter John Gatins also does not recommend his story for in-flight reading. “I’ve gotten emails from people saying:, ‘Man, I made the mistake of opening your screenplay on a plane,’ ” Gatins says with a laugh. His fictional concept is not too far from recent fact: In 2009, not one, but two pilots were arrested preflight at London’s Heathrow Airport after failing Breathalyzer tests. Both planes, one American Airlines and one United, were coincidentally headed for Chicago.

That basis in reality might be why Flight is taking off at the boxoffice. In fact, it’s impossible to avoid the aviation metaphors when describing the success of this $30 million action film. With Oscar buzz for Washington’s performance and an estimated $80 million domestic boxoffice take through four weeks, it’s soaring, flying high, and taking flight simultaneously.

However, as with the occasional airport experience, Flight didn’t exactly take off on time: Gatins’ ETD for his Flight was 1999; ETA on the big screen, more than 12 years later.

Gatins based his tale on two of his own worst fears: Getting killed in a plane crash and dying of an overdose. After moving to L.A. and living the hard-partying life as he struggled to become an actor, Gatins, 44, says he finally got sober at age 25 and started sketching out this story at age 31. He wanted to examine the conundrum of a successful, talented man who had functioned with addiction for years but was now “circling the drain both physically and emotionally.”

Gatins also sought to explore society’s desperate need to anoint heroes but remain blind to their human faults. The screenwriter compares Washington’s smart, arrogant Whip Whitaker to bicyclist Lance Armstrong in terms of being stripped of hero status once a tragic flaw is revealed.

Besides having to work out the puzzle for himself, Gatins also quickly discovered that Hollywood was not exactly waiting for this story—part plane-crash thriller, part character study of a troubled antihero. The script stayed in his back pocket for years, partly because of his own stop-and-start struggle to put together what he calls a personal Rubik’s Cube of an idea, and partly because he knew that an adult drama about substance abuse was a tough sell. “It’s like, ‘Show me comps of addiction movies that have made $100 million,’ ” Gatins says, describing the initial reaction of film executives to the idea.

Actors, however, always responded to the textured characters, Gatins adds. “Actors always said, ‘There is a way this movie could get made if we got an ensemble of actors together that kind of moved the needle,’” Gatins explains.

In the years since the idea began to take shape, Gatins pursued other film projects, including writing and directing 2005’s Dreamer: Inspired by a True Story, for DreamWorks. Around that same time, a partial draft of Flight was gaining traction at DreamWorks but got shoved to a back burner when Paramount acquired DreamWorks, also in 2005.

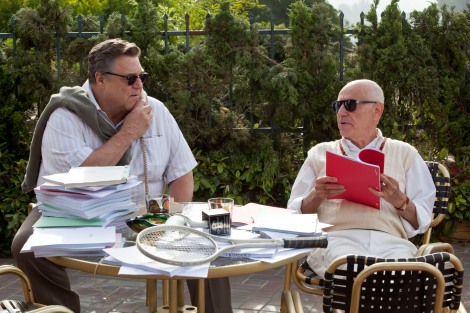

Flight came back on the radar in 2009, when Zemeckis’ producing partner, Jack Rapke, brought him the script and let the director know that Washington was interested. “So I called up Denzel and said, ‘I just read this. Are you really interested in doing this?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, are you really interested in this?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Well, let’s do it.’ ” (During this time, Gatins was also at work as one of the writers on the 2011 film Reel Steel, executive produced by Zemeckis).

Added Zemeckis:“Of course, that was fun. And then it got crazy. And then it got fun again.”

The “crazy” was coming up with a plan that would make Paramount willing to take a chance on an adult drama. In a nutshell: Keep the budget at $30 million, a tall order for a film that requires a jet to fly upside down.

“Here’s the thing: The guys who are running the studio, they love this kind of movie—we all grew up on these movies. That’s why we got into the business,” Zemeckis says. “Conventional wisdom is that people don’t generally go to see adult dramas. It’s sad that these are the hardest movies to market.

“When I approach a movie, my attitude is, I just want it to make $1 profit, then nobody gets hurt,” the director continues. “But Denzel and I realized that what we’d have to do is waive our fees and make the movie for the $30 million number that Paramount wanted. And then they basically said, ‘Go with God, and make the best movie you can.’ ”

Like Washington, Zemeckis declined to give his actual salary figure, but Washington says both artists were working at one-tenth of their usual pay for a major film. And, in term of amping up the visual sizzle while staying on budget, Zemeckis observes, “We’ve got maybe the greatest actor in the world, so that’s pretty great—you’ve got the spectacle of a Denzel performance, so that’s cool. And then what I can bring to the party is that I’ve got so many years of experience, I know a lot of great (visual effects) artists who can deliver, so I was able to bring them into the movie. That allows the movie to look a lot more expensive than it really is.”

Both the director and the writer acknowledge the movie might not have happened without the commitment of Washington, but the nuanced roles also attracted a celebrated supporting cast including Don Cheadle, John Goodman, and English actress Kelly Reilly, who portrays the vulnerable recovering addict who helps lead Whitaker to face his demons. “It’s a brave movie,” says Reilly. “They do things head on. It’s not cool or clever—there’s no vanity in it.”

For Zemeckis, Flight marks his first return to live-action cinema in 12 years after directing and producing films that use motion-capture technology, including The Polar Express and A Christmas Carol. He thinks too much has been made of this fact. “Making movies never really feels good, it’s always a lot of hard work,” he says. “But doing a live-action movie after not doing a live-action movie for a couple years, it didn’t matter. It’s kind of like riding a bicycle—it all came rushing back.”

For his part, Gatins hopes that Flight helps take the stigma off serious adult dramas when it comes to boxoffice potential. “That’s what the conversation has been like—will there be a turn back to these sorts of films, like the great cinema of the ’70s?” he says. “We were helped by True Grit and Black Swan and The Fighter—movies that had tougher issues at their core. This is a grownup drama.”