Pete Hammond is Deadline’s awards columnist.

Can’t we just end all this suspense about winners or losers and call it one massive tie this year? The 2012 crop of Oscar nominees, and films in general, is so impressively dense with quality it seems a shame the Academy has to pick just one winner in each category. But that’s the name of the game we play this time of year, and with ballots going out just as I had to turn this piece in, it is still a fluid situation as to just what the final results will be. With so many movies spread across many categories that are genuine contenders, a split vote resulting in some surprising twists and turns is possible, even though the various guild  awards give strong clues about industry sentiment. If the past is any indication, I am aware some readers might take these predictions as gospel and bet the farm on it in their Oscar pools, so I offer a disclaimer before we begin. I am not responsible for any monetary loss you might incur, nor do I expect 10% of any winnings. I am just trying to read the winds of Oscar after several months of analyzing every tea leaf. Here is where I have a hunch it stands, but please note I have made a few tweaks since the original version of these predictions were published in last week’s print edition of AwardsLine (I switched in production design and makeup/hairstyling). Results at BAFTA, WGA, and several other guild award shows have now been taken into account since then, but it is all still a crap shoot in one of the craziest Oscar years in memory.

awards give strong clues about industry sentiment. If the past is any indication, I am aware some readers might take these predictions as gospel and bet the farm on it in their Oscar pools, so I offer a disclaimer before we begin. I am not responsible for any monetary loss you might incur, nor do I expect 10% of any winnings. I am just trying to read the winds of Oscar after several months of analyzing every tea leaf. Here is where I have a hunch it stands, but please note I have made a few tweaks since the original version of these predictions were published in last week’s print edition of AwardsLine (I switched in production design and makeup/hairstyling). Results at BAFTA, WGA, and several other guild award shows have now been taken into account since then, but it is all still a crap shoot in one of the craziest Oscar years in memory.

BEST PICTURE

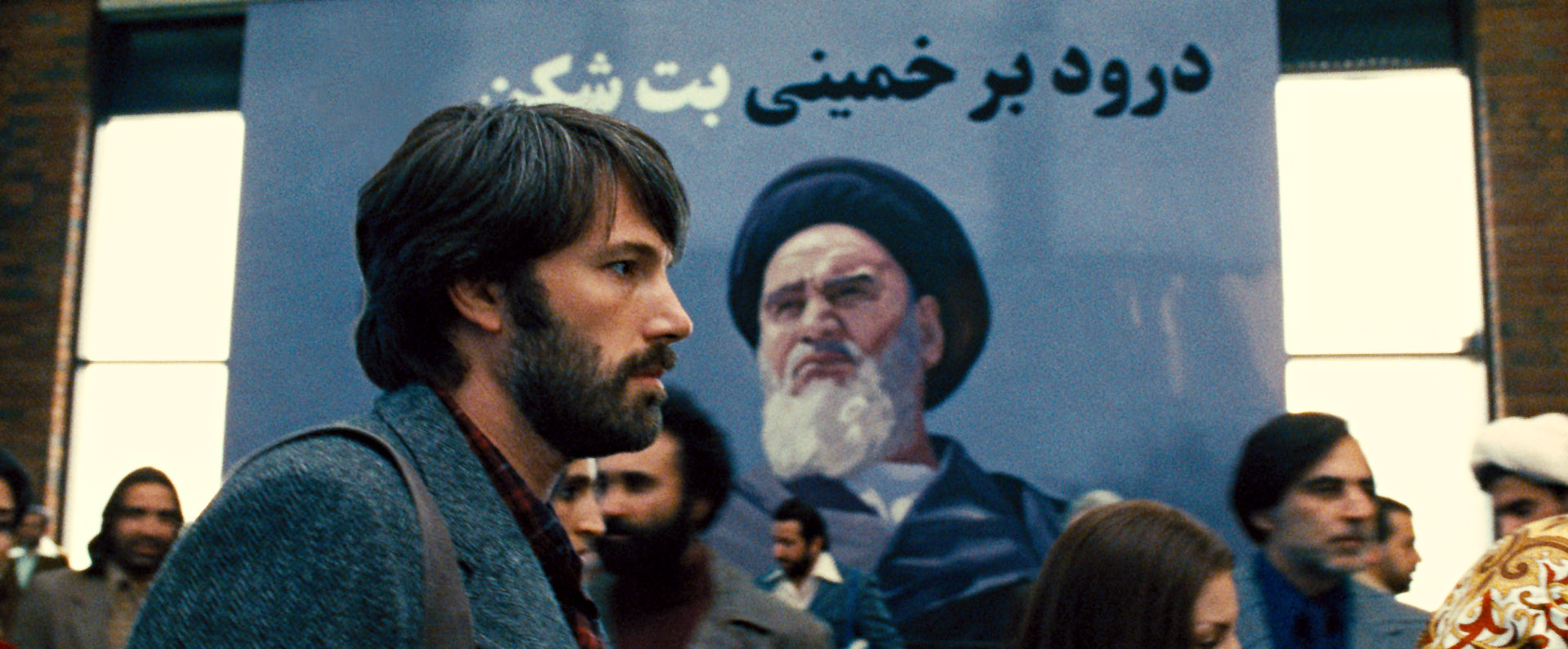

All season long, this has been about as wide open a race, and as competitive a field of contenders, as we have seen in many years. With nine nominees, the same number as last year, it has taken a while to figure out a surefire winner. But with key awards from the PGA, DGA, WGA, BAFTA and SAG, in addition to best picture honors at the Golden Globes and Critics Choice Movie Awards, Argo has clearly emerged as the frontrunner, a remarkable turn of events considering its director, Ben Affleck, was snubbed by the Academy’s directing branch Jan. 10. Oh, what a difference a few weeks makes. The big question is, can the Warner Bros. juggernaut maintain momentum and win Oscar’s top prize, even without that directing nomination? If so, it would be only the second film to win without a directing nom, following Driving Miss Daisy’s feat at the 1990 ceremony. With the best picture category holding the strongest possibility for success among Argo’s seven nominations, could it actually win here and nowhere else? Not likely, but it’s possible, especially in a year in which I think the Academy will be spreading the wealth. Lincoln, with a leading 12 nominations (a good, if not always correct, indicator), Silver Linings Playbook, and Life of Pi are probably still in the mix here as well but…

The Winner: Argo

The Competition: Amour, Beasts of the Southern Wild, Django Unchained, Les Misérables, Life of Pi, Lincoln, Silver Linings Playbook, Zero Dark Thirty

BEST DIRECTOR

With the quirky director’s branch going out of their way to snub DGA nominees Kathryn Bigelow, Tom Hooper, and DGA winner Ben Affleck, we know for sure we can’t count on the usual spot-on correlation between the DGA winner and the eventual victor in this category. Affleck actually would have been my prediction to win here, but, alas, he’s not even nominated, which means voters might very well be splitting their vote for director and picture this year — certainly not unheard of in recent years but increasingly rare. As directors of the two films with the most nominations, Steven Spielberg for Lincoln and Ang Lee for Life of Pi, are the likely frontrunners, with Silver Linings Playbook’s David O. Russell coming up on the outside. If initial frontrunner Lincoln has been eclipsed in the Best Picture race, this is the place voters could come to kneel at the Spielberg-ian altar. Or not. Lee’s triumph in even managing to bring the “unfilmable” Pi to the screen just screams “directing”, and that could play very well here.

The Winner: Ang Lee, Life of Pi

The Competition: Michael Haneke, Amour; Benh Zeitlin, Beasts of the Southern Wild; Steven Spielberg, Lincoln; David O. Russell, Silver Linings Playbook

BEST ACTOR

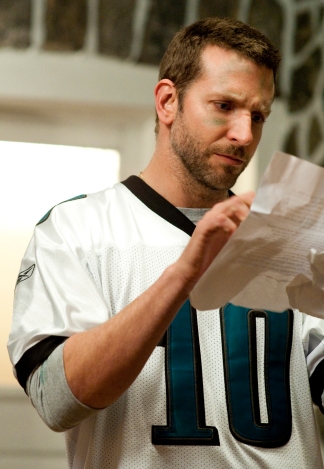

This is Daniel Day-Lewis’ to lose at this point. Playing such a well-known biographical figure is, of course, a big plus. But Day-Lewis brought a lot to the table and remains the guy to beat in an impossibly fine field of contenders. Day-Lewis’ biggest drawback is that he has already won this prize twice, and a third would be unprecedented for lead actors in Oscar history. Also no actor has ever won an Oscar for playing a U.S. president, another potential first. The Academy might want to reward equally deserving newcomers to the category like Hugh Jackman or Bradley Cooper instead, but judging from the pile of precursor awards Day-Lewis has already won, it looks like you can bet a very large pile of $5 bills that he will make Oscar history with honest Abe.

The Winner: Daniel Day-Lewis, Lincoln

The Competition: Bradley Cooper, Silver Linings Playbook; Hugh Jackman, Les Misérables; Joaquin Phoenix, The Master; Denzel Washington, Flight

BEST ACTRESS

I got this one wrong last year when Meryl Streep (The Iron Lady) beat Viola Davis (The Help), and this is another tough one. The race for lead actress is hotly competitive, with both Silver Linings Playbook’s Jennifer Lawrence and Zero Dark Thirty’s Jessica Chastain claiming other early awards and also impressing with strong performances (Naomi Watts is magnificent in The Impossible, but that film got no other nominations, putting it at a disadvantage here against four other actress nominees from Best Picture contenders). Plus, never underestimate the so-called “babe factor” (thanks to the Academy’s dominant male membership) that this category often, but not always, favors. A win here for either one could be a chance to give either of their movies an important award, while shutting them out elsewhere. The real wild card in this race is 85-year-old Emmanuelle Riva, whose performance in the foreign language film Amour has been widely praised and admired, particularly by her fellow actors, who comprise the Academy’s largest voting block. As the oldest Best Actress nominee ever (she actually turns 86 on Oscar Sunday), she could trigger a sentimental factor and a feeling that the others will have another shot someday. SAG champ Lawrence probably has the edge and is where the smart money’s going, but a split in this very fluid category could provide one of the evening’s most interesting stories. So going way out on a limb…

The Winner: Emmanuelle Riva, Amour

The Competition: Jessica Chastain, Zero Dark Thirty; Jennifer Lawrence, Silver Linings Playbook; Quvenzhané Wallis, Beasts of the Southern Wild; Naomi Watts, The Impossible

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR

In a category of five former Oscar winners (a first indeed), I could actually see five different, and logical, results. Christoph Waltz took the Golden Globe and BAFTA, Philip Seymour Hoffman was the Critics Choice, and Tommy Lee Jones won at SAG. Alan Arkin is playing an industry insider in the enormously popular Argo, and the Weinstein Co. has been effectively reminding everyone Robert De Niro hasn’t won an Oscar in 32 years or even been nominated in 21 years. He’s coming up on the outside as Silver Linings Playbook has become a sizable hit just passing $100 million over the weekend. Truly, toss a coin here. There’s no true frontrunner, and a logical route to victory is possible for each one of these veterans.

The Winner: Robert De Niro, Silver Linings Playbook

The Competition: Alan Arkin, Argo; Philip Seymour Hoffman, The Master; Tommy Lee Jones, Lincoln; Christoph Waltz, Django Unchained

BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS

Like the best actor race, this one has a clear frontrunner in Les Misérables’ Fantine, Anne Hathaway. Having won just about every precursor award including SAG and BAFTA, it looks like this year Hathaway will make it to Oscar’s stage without hosting the show. A video parody of her moving performance singing the signature “I Dreamed a Dream” went viral but shouldn’t stand in her way. If any of the other contenders have a shot, it’s definitely Lincoln’s Mary Todd, Sally Field. We know Oscar likes her — they really, really like her (she’s won twice) — but it appears to be Hathaway’s year in the winner’s circle.

The Winner: Anne Hathaway, Les Misérables

The Competition: Amy Adams, The Master; Sally Field, Lincoln; Helen Hunt, The Sessions; Jacki Weaver, Silver Linings Playbook

BEST ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

This is a very tough category with several worthy entries, all Best Picture nominees. Pulitzer Prize- and Tony-winning playwright Tony Kushner’s herculean efforts in finding the right tone and approach to Lincoln are well chronicled, and he has the solid endorsement of Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of the book Team of Rivals from which he drew a lot of source material. He is a major contender, even if Argo takes Best Picture over his film. A late-breaking controversy sparked by a Connecticut congressman over some of the facts in the film hit just as ballots reached voters hands and that could be a factor here. On the other hand, Chris Terrio’s meticulous and tricky work on Argo is impressive, and voters might want to reward the film’s script, especially if they are voting it Best Picture. That is usually how it works, but this is a weird year. Argo has also had its own fair share of criticism from some quarters for tweaking some of the facts for dramatic purposes. Of course voters may realize they aren’t voting for Best Documentary. David O. Russell’s funny and moving adaptation of Silver Linings is another strong possibility and recently took this prize from BAFTA, so it’s a three-way battle. But with its Best Picture likelihood…

The Winner: Chris Terrio, Argo

The Competition: Benh Zeitlin and Lucy Alibar, Beasts of the Southern Wild; David Magee, Life of Pi; Tony Kushner, Lincoln; David O. Russell, Silver Linings Playbook

BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

This is another category that seems widely split with no obvious frontrunner. But the three likeliest contenders would appear to be Django Unchained which won this award at Critics Choice, Golden Globes and BAFTA, Zero Dark Thirty which took it at WGA, and Amour, considering all three are also Best Picture nominees. That would indicate more widespread support among the entire Academy, which gets to vote in the finals. Both Quentin Tarantino’s Django and Mark Boal’s Zero Dark Thirty have been hit by controversy over their respective elements of treatment of slaves and use of torture, giving both of those former winners in this category more of an uphill climb to overcome negative publicity. That leaves an opening for the widely admired Amour, which could become the first to win both Best Foreign Language film and Original Screenplay since Claude Lelouch’s 1966 film A Man and a Woman, a movie that, like Amour, also happened to star the great Jean-Louis Trintignant. Django could well bring Tarantino his second writing Oscar, but…

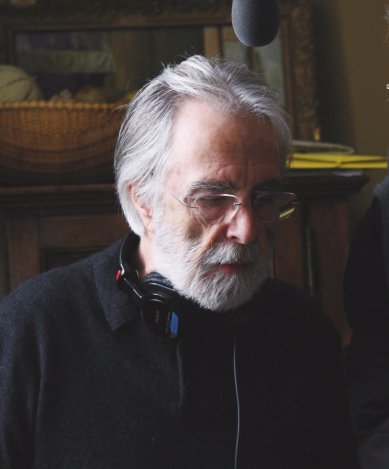

The Winner: Michael Haneke, Amour

The Competition: Quentin Tarantino, Django Unchained; John Gatins, Flight; Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola, Moonrise Kingdom; Mark Boal, Zero Dark Thirty

THE OTHER CATEGORIES

BEST FOREIGN LANGUAGE FILM

A strong group of movies, but the other four nominees have the misfortune of being named in a year that also includes Amour, which despite being a French film is actually the Austrian entry because of the nationality of its director, Michael Haneke. Winner of the Palme d’Or and just about every precursor prize this year, as well as being only the fifth film in Oscar history in this category also to be up for Best Picture, it would appear to be unbeatable here. But if any category has offered surprises in recent years, it is this one since you can only vote only if you prove you have seen all five entries.

The Winner: Amour (Austria)

The Competition: Kon-Tiki (Norway), No (Chile), A Royal Affair (Denmark), War Witch (Canada)

BEST ANIMATED FEATURE

Tim Burton, whose Frankenweenie was a critical hit but a box office disappointment, is overdue for Oscar recognition, and this one might be his most personal film yet. However, there are two other stop-motion entries in the category, including the acclaimed ParaNorman, which has been campaigned heavily, and the highly underrated and hilarious Aardman ’toon The Pirates, which by comparison has been well hidden by Sony. Two other Disney entries — Pixar’s Brave, which won the Golden Globe and BAFTA, and Disney Animation’s Wreck-It-Ralph, which triumphed at the PGA and Annies — could help split the studio vote with Frankenweenie, but I doubt it.

The Winner: Wreck-It-Ralph

The Competition: Brave, Frankenweenie, ParaNorman, The Pirates! Band of Misfits

A deserving group of nominees dealing with heavyweight topics are likely to lose to a fascinating and very human musical documentary about the resurrection of a singer long given up for dead who finally finds fame in the most unlikely of ways.

The Winner: Searching for Sugar Man

The Competition: 5 Broken Cameras, The Gatekeepers, How to Survive a Plague, The Invisible War

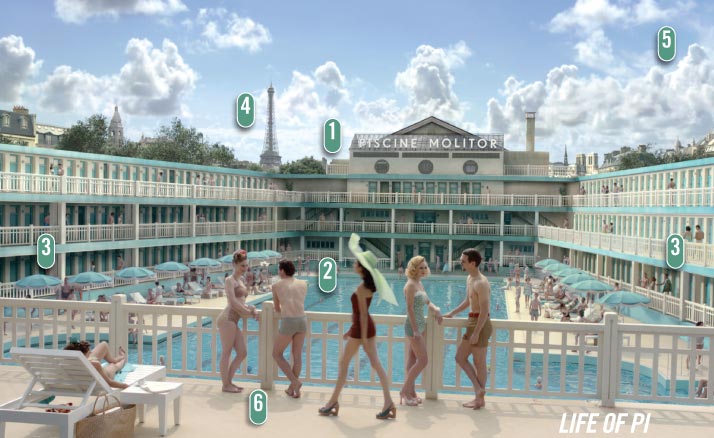

BEST PRODUCTION DESIGN

If there were a production more beautifully designed this year than Anna Karenina, I am not sure what it is, but reaction overall to the movie was mixed, meaning large-scale Best Picture nominees Les Misérables, Life of Pi, or Lincoln might sneak past it, but which one? For the sheer technical challenge of it all, I would say take another slice of Pi.

The Winner: Life Of Pi (Production Design: David Gropman; Set Decoration: Anna Pinnock)

The Competition: Anna Karenina (production design: Sarah Greenwood, set decoration: Katie Spencer); The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (production design: Dan Hennah, set decoration: Ra Vincent and Simon Bright); Les Misérables (production design: Eve Stewart, set decoration: Anna Lynch-Robinson); Lincoln (production design: Rick Carter, set decoration: Jim Erickson)

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

Life of Pi is considered a masterful technical achievement, and one of its chief attributes is Claudio Miranda’s stunning cinematography, which blends the CGI world with the real and makes it all a cohesive whole.

The Winner: Life of Pi, Claudio Miranda

The Competition: Seamus McGarvey, Anna Karenina; Robert Richardson, Django Unchained; Janusz Kaminski, Lincoln; Roger Deakins, Skyfall

RELATED: OSCARS: Cinematographers On Creating The Right Imagery

BEST COSTUME DESIGN

Two of the nominees here really scream costume design and deliver on all fronts: Mirror Mirror from the late Eiko Ishioka and Snow White and the Huntsman from frequent winner Colleen Atwood. There are also two more high-profile Best Picture nominees in the mix — Lincoln and Les Misérables — but this category often marches to the beat of its own drum, and this year the stunning work from Jacqueline Durran for Anna Karenina will likely stand above the rest when voters sit down to assess these contenders.

The Winner: Anna Karenina, Jacqueline Durran

The Competition: Les Misérables, Paco Delgado; Lincoln, Joanna Johnston; Mirror Mirror, Eiko Ishioka; Snow White and the Huntsman, Colleen Atwood

RELATED: OSCARS: Nommed Costume Designers Talk About Challenges

BEST FILM EDITING

This is sometimes a category where voters go their own way, such as last year when non-Best Picture nominee The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo shocked the frontrunners here and won its one and only Oscar in a bit of a surprise. This year, all five nominees are also up for Picture, so it should follow more closely to tradition. Because of its technical challenges, Life of Pi’s chances cannot be discounted, but this seems a place also to honor Argo for its tricky dance with tone and pace, although its editor William Goldenberg is competing with himself for Zero Dark Thirty. Still….

The Winner: Argo, William Goldenberg

The Competition: Life of Pi, Tim Squyres; Lincoln, Michael Kahn; Silver Linings Playbook, Jay Cassidy and Crispin Struthers; Zero Dark Thirty, Dylan Tichenor and William Goldenberg

RELATED: OSCARS: Nominated Film Editors Break Down Key Scenes

BEST MAKEUP AND HAIRSTYLING

This one’s almost a toss-up. Peter Jackson’s return to Middle Earth might normally have an advantage just because of the very nature of the film — unless voters want to reward the changing looks of Jean Valjean and Fantine in Les Mis which won at BAFTA.

The Winner: Les Miserables, Lisa Westcott and Julie Dartnell

The Competition: Hitchcock, Howard Berger, Peter Montagna, and Martin Samuel; The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, Peter Swords King, Rick Findlater, and Tami Lane

BEST ORIGINAL MUSIC SCORE

Of course Lincoln’s John Williams is a perennial nominee and winner already of five Oscars, while Skyfall’s 11-time nominee and recent BAFTA winner Thomas Newman is still looking for his first. But I have a feeling it’s between the masterful mix of Middle Eastern strains and orchestral score that Alexandre Desplat pulled off in Argo versus first-time nominee Mychael Danna, who earned a nomination for his elegant and stirring score in Life of Pi, as well as an original song nom.

The Winner: Life of Pi, Mychael Danna

The Competition: Anna Karenina, Dario Marianelli; Argo, Alexandre Desplat; Lincoln, John Williams; Skyfall, Thomas Newman

BEST SONG

Oscar host Seth MacFarlane cowrote one of the nominated songs, the sprightly tune from Ted, and it has a shot because it is the type of upbeat melody that has won here in recent years. If a Muppet can win last year, why not a stuffed bear? The one and only original song in Les Mis, “Suddenly”, isn’t all that memorable compared to the rest of the score. We’re going with the frontrunner and Golden Globe winner, Skyfall, which should make Adele the latest pop star to successfully infiltrate this category. It also would be the first-ever James Bond song to actually win, appropriate in 007’s 50th year, don’t you think?

The Winner: “Skyfall” from Skyfall, Adele Adkins and Paul Epworth

The Competition: “Before My Time” from Chasing Ice, music and lyrics by J. Ralph; “Everybody Needs a Best Friend” from Ted, music by Walter Murphy, lyrics by Seth MacFarlane; “Pi’s Lullaby” from Life of Pi, music by Mychael Danna, lyrics by Bombay Jayashri; “Suddenly” from Les Misérables, music by Claude-Michel Schönberg, lyrics by Herbert Kretzmer and Alain Boublil

RELATED: OSCARS: Best Original Song Race Handicap

BEST SOUND EDITING

The sound categories are rarely completely understood by the membership at large that gets to vote in all categories, but again, the technical achievement and challenges of Life of Pi probably prevail over a worthy field that could include another bow to James Bond, or a tip of the hat to Argo as part of its Best Picture booty, but probably won’t.

The Winner: Life of Pi, Eugene Gearty and Philip Stockton

The Competition: Argo, Erik Aadahl and Ethan Van der Ryn; Django Unchained, Wylie Stateman; Skyfall, Per Hallberg and Karen Baker Landers; Zero Dark Thirty, Paul N. J. Ottosson

RELATED: OSCARS: Sound Editing and Sound Mixing Nominees Often Overlap

BEST SOUND MIXING

Life of Pi might very well take the sound category, but here musicals often triumph, and what greater sound mixing achievement was there this year than blending nearly unprecedented live singing with other sound elements in Les Mis? Among other things, they had to bring an entire orchestra in during post to match the songs.

The Winner: Les Misérables, Andy Nelson, Mark Paterson, and Simon Hayes

The Competition: Argo, John Reitz, Gregg Rudloff, and Jose Antonio Garcia; Life of Pi, Ron Bartlett, D.M. Hemphill, and Drew Kunin; Lincoln, Andy Nelson, Gary Rydstrom, and Ronald Judkins; Skyfall, Scott Millan, Greg P. Russell, and Stuart Wilson

BEST VISUAL EFFECTS

This one’s a runaway. The biggest sure thing on the ballot. Even at the Oscar Nominees Luncheon when the name first came up, there was a big whoop and applause from the voter-heavy audience. And it ran over the competition at the VES awards and BAFTA, too.

The Winner: Life of Pi, Bill Westenhofer, Guillaume Rocheron, Erik-Jan De Boer, and Donald R. Elliott

The Competition: The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, Joe Letteri, Eric Saindon, David Clayton, and R. Christopher White; Marvel’s The Avengers, Janek Sirrs, Jeff White, Guy Williams, and Dan Sudick; Prometheus, Richard Stammers, Trevor Wood, Charley Henley, and Martin Hill; Snow White and the Huntsman, Cedric Nicolas-Troyan, Philip Brennan, Neil Corbould, and Michael Dawson

BEST DOCUMENTARY SHORT SUBJECT

As usual, this category has a strong list of heavyweight topics, but it’s likely between Mondays at Racine, a touching film about a beauty shop that opens its doors once a week to cancer patients, and Open Heart, about a group of Rwandan children being flown to the only free medical center in Africa for treatment of heart disease. In a year that features more than one contender dealing with the pain and problems of aging, Kings Point might also have a shot. This is a category where you can only vote in person at special screenings of all five (four of the five films are from HBO which dominates here).

The Winner: Open Heart

The Competition: Inocente, Kings Point, Mondays at Racine, Redemption

BEST ANIMATED SHORT FILM

This is a very rich category, and for the first time, DVD screeners of the contenders here and in live-action short (as well as feature docs) were sent to the entire membership, rather than allowing voting only at special screenings where all five noms are shown. With a Simpsons ’toon from Fox, as well as a Disney Animation Studios title in the mix, those studios with large numbers of Academy voters could have the advantage, especially if those studios’ Academy members stay loyal to their home team. That could put others here — such as the charming and remarkably accomplished British student stop-motion animated entry Head Over Heels, about a longtime married couple who have grown apart literally and figuratively — at a disadvantage. And Disney’s Paperman is equally wonderful giving it frontrunner status, as it also played theatrically earlier in the year. This is a really tough choice. However, Goliath doesn’t always beat David, so on a hunch….

The Winner: Head Over Heels

The Competition: Adam and Dog, Fresh Guacamole, Maggie Simpson in The Longest Daycare, Paperman

BEST LIVE ACTION SHORT FILM

A generally intriguing group of films, most with a strong international flavor, provide great showcases for some potentially major new directors. Particularly cinematic are Death of a Shadow, Asad, and Afghanistan’s remarkably fine and memorable entry, Buzkashi Boys.

The Winner: Buzkashi Boys

The Competition: Asad, Curfew, Death of a Shadow, Henry