Cari Lynn is an AwardsLine contributor. This article appeared in the Feb. 6 issue of AwardsLine.

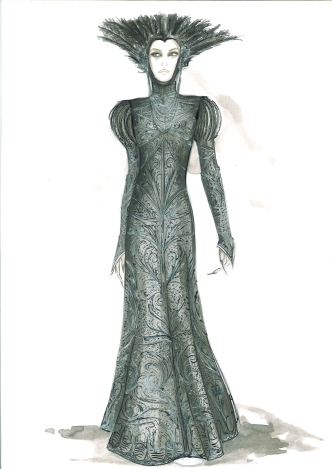

Colleen Atwood | Snow White and the Huntsman

No stranger to the Oscar race with three wins (for Alice in Wonderland, Memoirs of a Geisha, and Chicago), plus another seven nominations, Atwood didn’t originally plan on a career in costume design. She’d gone to art school to study painting, but when she became pregnant in high school, her path diverged to retail fashion so she could earn a living. It wasn’t until her daughter was in high school that Atwood moved to New York and took a film class, where she found herself the go-to person for sets and costumes for her fellow students. Her first break was in 1980, working on sets and props for Ragtime.

Why it’s Oscar-worthy: “Any time you’re able to design a whole new world it sets it apart,” she says. “Personally, my work on Snow White and the Huntsman is some of the most interesting I’ve ever done because I got to use new and innovative materials and applications and shapes. To be nominated by your peers is fabulous and exciting because these are the people who really scrutinize your work, whereas everyone else can have an emotional experience to the costumes, but that’s pretty tied into the movie.”

The showstopper: “I was asked to do a presell image, so I designed a feathered, raven cloak for Queen Ravenna (Charlize Theron). All the feathers were hand-trimmed, and I worked with an amazing milliner in London so that, like a real bird, all the feathers go in different directions and catch the light in an amazing way.”

Biggest challenge: “The fact that we manufactured 2,000 costumes. We had two armies designed from the ground up, three courts, peasants, scary creatures, and dwarves, where everything had to be scaled down to size but still be realistic. Also, Snow White had to wear the same costume throughout much of the movie, and you couldn’t get tired of looking at it, plus it had to go through variations. When I found out she was running through the woods, I thought, We’re going to get sick of seeing the same dress full of mud. We decided to put in the story that the huntsman trims the dress, and I put Snow White in leggings underneath. After the dress is trimmed, I love what happened—it’s a look young people could associate with, and on practical level Kristen Stewart does a lot of her own stunt work so the leggings protected her from the branches and cold and elements of the forest.”

How would you dress the Oscar statuette?: “The raven cape would look great with the gold body. And a crown. We used an awesome Gothic crown in the movie.”

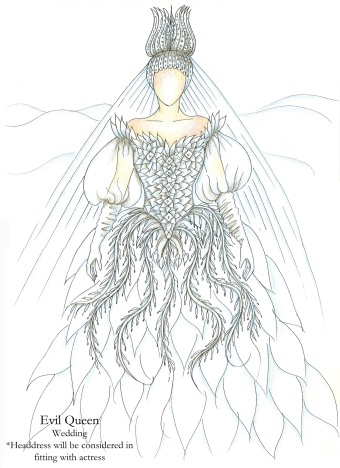

Eiko Ishioka | Mirror Mirror

With a previous Oscar for Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1992, a Grammy for the 1986 Miles Davis album cover Tutu, and a Tony nomination in 1988 for M. Butterfly, acclaimed Tokyo-born designer Eiko Ishioka passed away of pancreatic cancer prior to learning of her Oscar nomination for Mirror Mirror. Hailed by The New York Times as one of the foremost art directors in the world, Ishioka also has work that is featured in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. We spoke with Mirror Mirror director Tarsem Singh on the legacy of a pivotal designer, with whom he collaborated on all of his films.

Why it’s Oscar-worthy: “Eiko was a hell of an inspiration for us,” Singh explains. “Her verve flows out from her. Her DNA is completely in this film. You never had to say, ‘Think outside the box’ to Eiko. She belonged to a different planet. Usually people pull references from other films or research, (but) she never did that. She’d pull a photograph of an animal and say, ‘When the lizard is agitated, this is what it does with its neck.’ Her inspiration comes more from the natural history museum than any fashion magazine.”

The showstopper: “The wardrobe was written into the script—Eiko took my belief so viscerally. So if I say, ‘Let’s have a costume ball and make the queen stand out,’ she puts everyone in white on white and makes it an animal theme. Then there’s the Battleship game played with people’s hats. She does things I don’t think about until I see it, and I realize that every idea I talked about was incorporated. Then there are the dwarves. I wanted them to do fighting and didn’t want it to look CGI, but because this movie is also for children, the fighting couldn’t be aggressive. One of my biggest problems was solved by Eiko in a single conversation when she thought of doing accordion legs. We also discussed how the dwarves’ individual personalities had to come out through the clothes, but at the same time, they still needed to look like one group. So Eiko decided everyone’s personality should be in their hat.”

Biggest challenge: “Eiko was never fond of the practical. She would make what filmed the best, but it may not have moved. The toughest was for the dwarves—we didn’t want to have a Disney look, but they still had to look like a gang. Then, the Queen’s (Julia Roberts) wedding dress took a team to move it, and we made several dresses to shoot from different angles. If Julia was sitting, there was one dress, another for when she was in the coach. I was trying to make things easy for Eiko because she was undergoing cancer therapy, but she doesn’t know easy. She’d make seven choices of everything; I’d pick one, and then she’d present seven more variations on that. We spoiled her and said, ‘Let her have her time.’ It does make it more difficult for actors though—take a step in this (version of the costume), sit in that one, say your line in that one.”

How would Eiko dress the Oscar statuette?: “It’s so hard to try to guess. You would never tell Eiko what to make! I imagine she would have done something that would’ve been very hard to lift. If someone complained it was too heavy, she would have said, ‘You go put on weight then!’ ”

Paco Delgado | Les Misérables

Trained in set and costume design at the Institut del Teatre of Barcelona, Delgado has worked extensively with Spain’s most famous director, Pedro Almodóvar, on 2004’s Bad Education and 2011’s The Skin I Live In, as well as on Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Oscar-nominated Biutiful in 2010. In a twist of fate, Delgado met director Tom Hooper (Les Misérables, The King’s Speech) when they worked together on a Captain Morgan TV ad, and now Delgado has earned his first Oscar nomination for the epic film adaptation of the longest-running musical in history.

Why it’s Oscar-worthy: “This is about the history of France, but also about the history of the Western world,” Delgado says, “and it was a big responsibility to create this world, but I also had to remember I was doing a musical with drama, and I needed to have color and fantasy.”

Biggest Challenge: “We created 1,500 new costumes, out of a total of over 2,000 costumes, and many of them we had to break down with mud, grease, sand, brushes, and blowtorches because we wanted to reflect how poverty-stricken Paris was at that time. (In my research) I learned they used an amazing secondhand market where clothes were sold and resold and resold again until they were rags. Also, Tom and I had discussed a leitmotif, so I evoked the colors of the French flag throughout, using blue costumes in the early factory scene, then red for the revolution, and then moving to white for the wedding and nunnery scenes. Also, there’s always a fight with the budget and with time.”

The showstopper: “I wanted to try to interpret personalities and characters through the costumes. In Victor Hugo’s book, Fantine is coquettish and beautiful and had some views of the petty-minded society, so I wanted her factory dress to belong to her lost past. [Ed. note: Fantine’s dress was pink in the scene, in stark contrast to the other factory workers in drab blue.] It was all hand-embroidered and had a level of craftsmanship that would make Fantine appear as an outsider among the rest of the women.”

How would you dress the Oscar statuette?: “He already looks so sexy naked. After all, every woman and even every man wants to bring him home. I would do a version of the sexiest dress ever, like the transparent glittering dress that Marilyn Monroe wore at President John F. Kennedy’s birthday at Madison Square Garden. It’s very appropriate for Oscar who only appears in his birthday suit—and I’m very proud I have been invited to his 85th birthday!”

Joanna Johnston | Lincoln

Johnson’s biography reads like a “best films” list spanning more than three decades. She cut her teeth as an assistant costume designer on Roman Polanski’s Tess in 1979 and went on to be the go-to designer for Robert Zemeckis (Forrest Gump, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Cast Away), M. Night Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable), and Steven Spielberg (the Indiana Jones franchise, The Color Purple, Saving Private Ryan, War Horse). Somehow, though, Oscar evaded this British designer until now, with her much-lauded Lincoln, Johnston’s eighth Spielberg-directed film.

Why it’s Oscar-worthy: “I suppose it hits a button with the balance of the piece as a whole,” she says. “I think the work is quite quiet—most of my work is not showcase-y but relatively character-driven. The academics and the historians seem to be happy at the accuracy, and my thought is (voters) normally go for the very expansive and forward-projecting and not necessarily the things that are understated, so all I can say is I’m really, really pleased.”

The showstopper: “I don’t have a piece designed to be a showstopper—it’s not that kind of film; Lincoln himself is the most iconic, but if there’s one that pushes above in my mind, it’s Mary Todd’s cream dress when she goes to the theater. You see it as a whole dress, and I based it off of two dresses of hers that I saw in portraits and fused together. I embellished the neckline and the sleeves because I wanted to do something to help Sally Field’s physicality get more into Mary Todd’s physicality, so I depicted Mary Todd’s affectation of fussiness in her dress.”

Biggest challenge: “The whole film! Each film is unique, but this is a completely different film, a different creature than anything else—it had its own character and rhythm and roots and had a very long gestation period of eight years. I was involved to a tiny degree over a six-year period.”

How would you dress the Oscar statuette?: “I would keep him as he is. I don’t think he could be improved—although I think he’d look kind of cool in armor, beautiful armor with a lot of tooling.”

Jacqueline Durran | Anna Karenina

A favorite collaborator of director Joe Wright’s, British designer Jacqueline Durran has garnered two other noms for Wright’s Atonement and Pride & Prejudice. Not bad for a designer who says she couldn’t understand why Wright had even asked to interview her for his first feature, Pride & Prejudice, given that Durran hadn’t previously done pre-20th-century designs.

Why it’s Oscar-worthy: “I think it’s the whole thing, how all the elements mesh together and become such a complete vision,” Durran says. “The way they move through the theater and the colors and the costumes, we all benefit from each other’s work. Joe had such a strong vision; he always had the idea that the film would be stylized, and in our first meeting he said he wanted to concentrate on silhouettes. We got to talking about how 1950s couture is about silhouettes, and how dramatic and beautiful it was, and from there it seemed we could combine 1870s dress with elements from the ’50s.”

Biggest challenge: “One part is that Joe is a challenging director because he pushes you to do more, to rethink things or to come up with different ideas. The other part is the idea of Anna Karenina, you hear it and you say, ‘Oh, god. It’s such a big idea.’ She’s got to look beautiful, the world has to be beautiful, you have to capture this luxurious beauty, and for that I had to raise my game. You feel you have something to live up to.”

The showstopper: “My personal favorite is the cream dress in the tea room in Moscow—I thought it really suited Keira Knightley, and also it was the most fully fledged version of the 1950s/1870s combo, with traditional skirt and then a pillbox hat. There’s no point in trying to make a stylized statement if it doesn’t end up looking like anything, and this came together. However, I do think the overall show-stopper has to be the ball because of all the elements there—26 dancers, in what I call ‘sour pastels’, surround Anna Karenina, all in black, and Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), all in white.”

How would you dress Oscar: “In diamonds and furs.”