Paul Brownfield is an AwardsLine contributor. This article appeared in the Dec. 12 issue of AwardsLine.

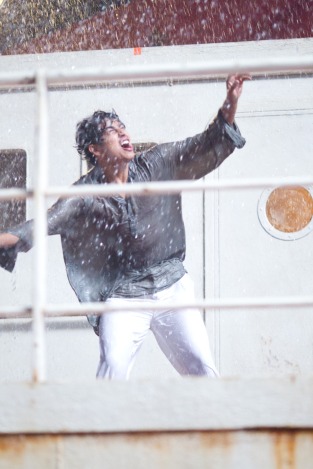

The tank could hold some 1.7 million gallons of water, and it made waves you could surf on, says Suraj Sharma, the 17-year-old star who spent long hours in this fabricated ocean. The motion of the water could be programmed to affect the turbulence of troubled seas or a sudden calm, the swells only lapping at the makeshift raft on which sits a boy adrift in the middle of the Atlantic. He is alone with his thoughts—but not strictly alone, because the lifeboat to which his raft is attached is occupied by a Bengal tiger.

“I’ve never seen water done well in a movie, and I’m doing 3D. Water is the main show,” says director Ang Lee, discussing the challenges of adapting Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi on open waters.

To hear Lee talk about the torque machines and energy-dissolving technology that enabled him to choreograph the motion and shape of the waves is to begin to understand what he means when he says the ocean, in the story, represents “the visualization of Pi’s internal feelings.”

“To shoot in water,” Lee says, “either you go through suffering the ocean, and not much gets done, or you create something like a bathtub,” with the water bouncing back and forth through the frame.

Lee, an Academy Award winner for Brokeback Mountain, wanted neither of these things. He wanted an actual physical environment in which to portray an experience that ventures into magical realism.

Thematically, Life of Pi is a story that asks its readers to consider what is illusory and what is real—and whether a fine distinction matters. It is part picaresque narrative, part allegory. “We view the whole thing as a film about stories and storytelling. How stories get us through life,” says screenwriter David Magee.

But movie magic had to do some evolving before Life of Pi could hit theaters. Lee’s film follows a curious and adventuresome teenage boy, nicknamed Pi, whose family owns a zoo in Pondicherry, India, where the many exotic creatures include a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker.

From these idyllic beginnings, the story soon turns apocryphal if not Biblical: When the family decides to leave India and relocate the zoo to Canada, they all set sail on a cargo ship that capsizes in the middle of the Atlantic. The sole survivors are Pi and four animals, huddled on a lifeboat—a zebra, an orangutan, a hyena, and the tiger. Soon enough (see under: Darwin, Charles) the allegorical framework is made apparent: Man and beast must learn to coexist in a horizonless expanse otherwise known as the middle of the ocean.

In the book, as in the film, the story is told from the point of view of the adult Pi, now living in Canada. As played by Irrfan Khan, the adult Pi retells his spiritual, emotional, and physical coming-of-age quest to a writer who while traveling in India has heard of the story secondhand.

Lee, even after completing the film, concedes that “it’s very hard to articulate what it’s about.” He calls it a “provocation for your imagination,” which is necessarily elliptical, given that the essential logline is that the story revolves around a tiger and a boy learning to coexist in the middle of the Atlantic.

Producer Gil Netter says the novel had already been passed on by every major studio, including Fox, when Fox 2000 president Elizabeth Gabler signed on to the project in 2002. The consensus had been that it was too difficult to realize as a movie. Netter optioned the book with screenwriter Dean Georgaris (the idea being that Georgaris might adapt it)). Netter says he and Georgaris pitched Gabler on Pi’s transcendent themes.

The book was already selling itself as a literary sensation, winner of the Mann Booker Prize, which didn’t much solve the problem of just how to make it into a movie. The challenge perennially boiled down to three words: Boy. Tiger. Ocean. Along the way, other words and phrases would arise, like “recession” and “no star potential,” neither of which dissuaded Netter, the producer of such films as The Blind Side, Marley & Me, and Water for Elephants. All of those movies are often called “heartwarming” or “uplifting” or “family-oriented.” Netter saw the same potential for Life of Pi. In the end, he also credited “the dogged enthusiasm and determination” of Gabler and 20th Century Fox executive vp Victoria Rossellini.

Some of the directors who attached themselves to the project went further than others. M. Night Shyamalan signed on initially to write and direct, and years later Alfonso Cuaron (Children of Men) circled the film, but no one before Lee got as far as Jean-Pierre Jeunet, the distinctive French director of such films as Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children.

Jeunet completed a script, which Netter says was more of a fairy-tale interpretation. “He wanted to shoot on the ocean, with live animals,” Netter explains, speaking with a wry delight. “To say that the studio was a little nervous is an understatement.”

By 2008, seven years after the book’s film rights had first been optioned, Lee was immersed in flower power and hippiedom as he readied his 2009 film Taking Woodstock. Around that time, Lee says, he got a call about Life of Pi from Tom Rothman, then cochairman of Fox Filmed Entertainment.

“He said, ‘It’s a family movie,’ ” Lee recalls of their initial conversation. “I said, ‘What do you mean, family movie?’

“In a strange way, it’s like the book,” Lee continues. “Yann Martel told me he thought he wrote a philosophical book for adults. He didn’t know why teenagers connect to it. It looks like they might with the movie, too.”

Lee was in postproduction on Taking Woodstock, when Fox came back to him to direct Life of Pi. Admittedly, Lee says, the book haunted him, and the question of “how do you crack this thing?” began to take hold of his imagination, particularly the prospect of telling a story as a 3D experience. As Lee puts it, the question was, “How do you examine illusion within illusion? We all know movies are based on illusions—the image, this emotional ride. How do you do that while you’re examining the power of storytelling?

“I thought of 3D maybe adding another dimension,” Lee continues. “What doesn’t make sense could make sense. And I thought of the older Pi telling stories and having the first person going through the story while the third person (is) examining it, but they’re the same person.”

This was months before James Cameron’s Avatar hit the theaters and promptly advanced the cause of 3D beyond movie gimmickry and into the realm of storytelling art. “It’s very daunting,” Lee says of shooting 3D. “You cannot trust anything people tell you, because it could be wrong, because it’s so new. And the audience hasn’t had a relationship with it yet.”

According to producer Netter, “Fox was challenging us all to figure out how to make this a four-quadrant international family movie. In order for that to have a chance at working, it’s got to feel like an event. So in the discussions to figure out how to event-ize it came the 3D discussion, and then Ang was smart enough to come up with a philosophy of how he could approach doing that.”

Netter jokes that he referred to one particular room on the set of Life of Pi as the Beautiful Mind room—it was where Lee had meticulously diagrammed “completely from top to bottom, all the way around the room every single detail of fact that needed to be known,” Netter says, down to the changing pallor of Pi’s skin as he endures a life at sea and the gradual aging of the oars.

The Taiwanese-born Lee had not shot in his home country since making his 1994 film Eat Drink Man Woman. The Life of Pi production was based in an abandoned regional airport in Taichung, which was converted into soundstages with an international crew of 150, some of whom enrolled their kids in schools in Taiwan during the year they were making the movie.

“Last time I tried to bring the American independent way, like New York independent filmmaking, back to Taiwan,” says Lee, juxtaposing his location shoots 20 years ago for Eat Drink Man Woman with the mini-studio he created for Life of Pi. “I was there alone. I just tried to bring the method there. This time I brought Hollywood.”

Thanks! Really wanted to know the film was made. :)